By Emily Ostertag – [email protected] – Staff Writer | April 8, 2015 |

The train stops. Everyone files out. Passengers form a line as a Nazi soldier begins checking their papers.

Irma Cantor, a young woman of 19, tries not to let others see her panic. She is missing some identification. The soldier pulls passengers from the line. She knows she’s next, but stands firm.

Were it not for the train’s conductor, Sharon Fahrer’s mother wouldn’t have escaped Berlin in 1939.

She required sponsorship for her move to London, England, and as many European Jews understood, their lives depended on this.

“Come on, we need to go. The train has to keep going,” he told the Nazi soldier while hurrying the remaining passengers back on board.

Irma’s daughter, Fahrer, lives in Asheville, but has deep family roots in working-class Germany. Relegated to janitorial and managerial work over apartment buildings, her mother learned the profession of cleaning at a young age. Little did she know, these skills would eventually buy her a ticket out of hell in the form of a domestic visa.

Similar stories can be found in many Jewish-Americans’ family histories. While bravery, resourcefulness, and luck saw many out of Europe during World War II, these same qualities put them at the forefront of industrial growth and commerce in the post-Civil War South, said Leonard Rogoff.

“The era of mass Eastern-European migration was from about 1880 to 1920, and this is also the era of railroad development,” said Rogoff, historian for the Jewish Heritage Foundation of North Carolina and author of Down Home. “So, if you want to see where Jews live, see where the railroads go. The railroads spurred the growth of an industrial and urban economy.”

For Fahrer’s mother, skills like domestic cleaning were learned out of necessity. Other families brought knowledge of textile production, scrap-metal collection, and simple trades like reusing rags.

From Russia, Ukraine, Germany and Poland, Jewish immigrants made cosmopolitan impressions on the growing towns they made home. In the 1880s and 1890s Asheville experienced its first migration of European Jews who, as Rogoff explained, introduced their trades into the still-agrarian economy of the new south.

Mill towns developed along railroad lines, as cotton, grain and other agriculturally-fueled mills moved closer to the fields that sustained them. Jewish immigrants became a vital cog in this new economic machine by providing services to farmers on their market days.

Some of the first Jewish families who settled in Asheville supplied clothing, groceries and other goods to market-goers, Rogoff said. Solomon Lipinsky, among others, owned small businesses like Bon Marche, a department store located in what is now the Haywood Park Hotel.

“Yes, I would say the majority of them were small business owners. The reason for that being, they had so many restrictions in Europe where they came from,” Fahrer said, owner of History at Hand and co-creator of “The Family Store” exhibit. “They weren’t allowed to own land, you know, they could only be in certain occupations.”

For early Jewish residents, adaptation was key. Farmers came to market on Saturday, the day of Shabbat. In Judaism, this is the day of rest — generally excluding work and money handling — but for these small business owners it was the busiest day of the week, Fahrer said. Many chose to stay open, while some sacrificed their income for religious observance.

Remaining kosher in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was difficult for those who didn’t live in urban places. For Asheville’s Jews, this meant getting their kosher products shipped from Charlotte or Cincinnati, Fahrer explained. But with poor refrigeration came spoilage.

Compromise became a way of life, and in Asheville during the 1890’s Jews from different denominations joined into one congregation, despite their varied views.

Throughout the centuries, Jewish peoples have fled their homelands due to persecution, and eventually found refuge in America, Fahrer said. Sephardic Jews fled Spain and Portugal during the Inquisition. Many German Jews left after the fall of Napoleon. In the late 19th century Eastern-European Jews escaped the Pogroms, and during WWII, those who could, fled the Holocaust.

Like the Lipinsky and Witlock families of Asheville’s first Jewish community, many came from Eastern Europe, where Orthodox Judaism was traditional. But for others, that wasn’t so. In 1891, these Jewish families founded Beth Ha Tephila, as a means to encompass everyone’s form of worship. It was the first synagogue in Asheville, Fahrer said. Now one of three, it stands on Liberty Street, as its original location was demolished during an urban renewal project in the 1960s.

“By 1896 another congregation was formed, that you would say, would be more Orthodox, or more like the worship of the Eastern European Jews,” Fahrer said. “They felt that the worship at Beth Ha Tephila was getting too assimilated and they wanted more of the traditions they were used to.”

Now with two synagogues, this small community, which existed modestly, had inadvertently given itself more presence. During the rise of anti-Semitic culture, recurring instances of religious prejudice began to threaten Asheville’s community.

In the 1930s, William Dudley Pelley made his way to Asheville, spreading his campaign of hate and anti-Semitism, Fahrer explained. He was a self-proclaimed “American Hitler” with a following called the Silver Shirts. Besides more engrained societal prejudice, such as banning Jews from country clubs, hotels, and other recreational places, Pelley’s actions made it necessary for Asheville’s community to form a safe meeting place. In 1941, the Jewish Community Center was founded in an old house off of Charlotte Street. The same building stands today, but has since expanded.

The smallest Jewish community to support a Jewish community center, Asheville provides a supportive atmosphere to many diverse groups. This phenomenon, linked to diaspora by many, may be a result of cultural networking and a refusal to be isolated, Deborah Miles explained.

“People have family all over the world, and you use family as a way to build connections,” said Miles , director of UNC Asheville’s Center for Diversity Education. “The isolation of the community is what had brought about all the connections.”

Asheville’s Jewish history may not be unique, and the community — currently at about 2,500 — may not be huge, but from humble beginnings as peddlers and merchants, their children’s success is a testament to the community’s sheer resourcefulness and drive.

Still showing through, remnants of Asheville’s past linger in historic sectors. A downtown of purpose, as Fahrer put it. Maybe it’s a good thing that Asheville hasn’t really changed too much.

Latest Stories

- Tribal political activities surge due to Lumbee tribes request for federal recognition

- Learn a Language!

- Questions On the Quad Episode 11

- What Do Blue Banner Staff Listen To?

- Asheville residents at odds over U.S. financial assistance to Ukraine

- The UNC Asheville Saber Club’s duels remain, moved to AC Reynolds Green

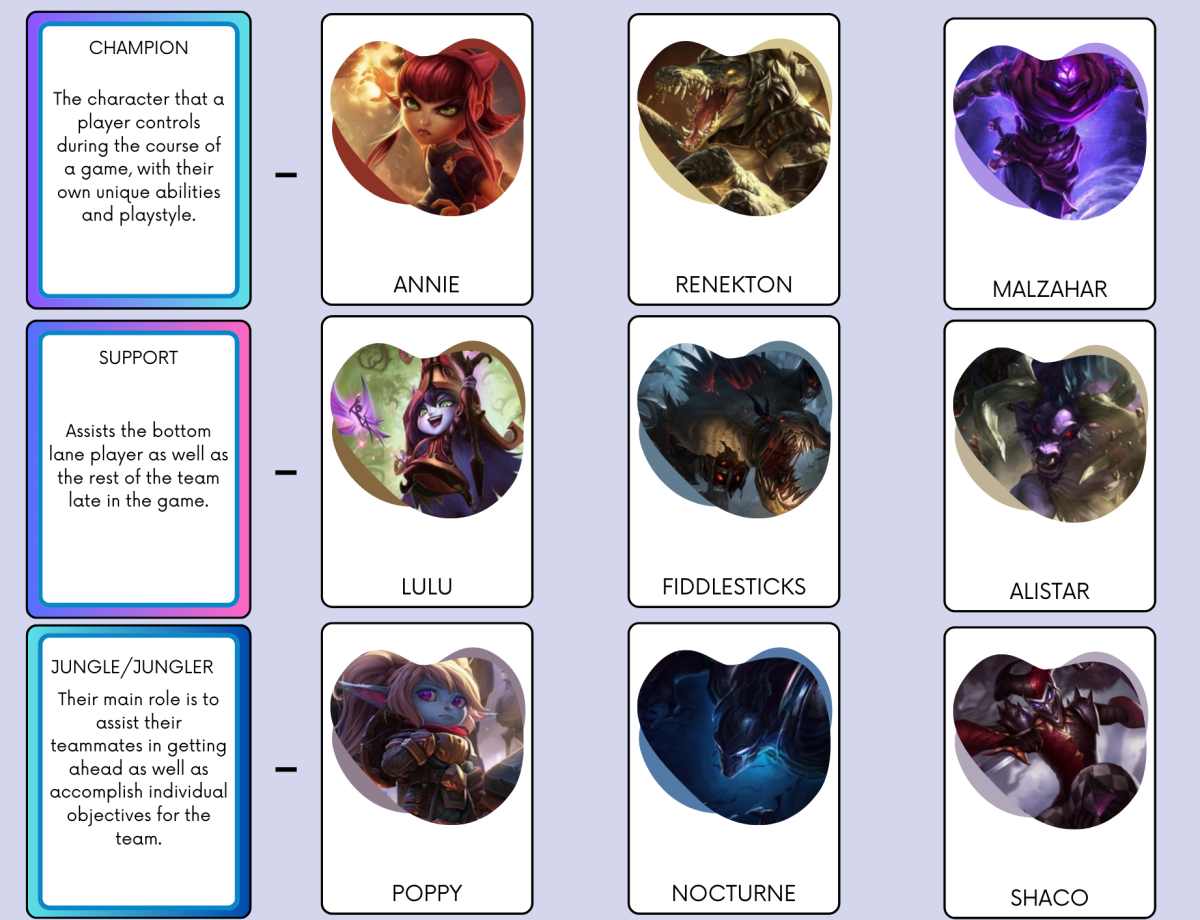

- UNCA League of Legends takes first in stunning finals match against HPU

- From passion to professional play: How a UNCA League of Legends MVP hit their stride

- Old UNCA sorority still has its footprints on campus

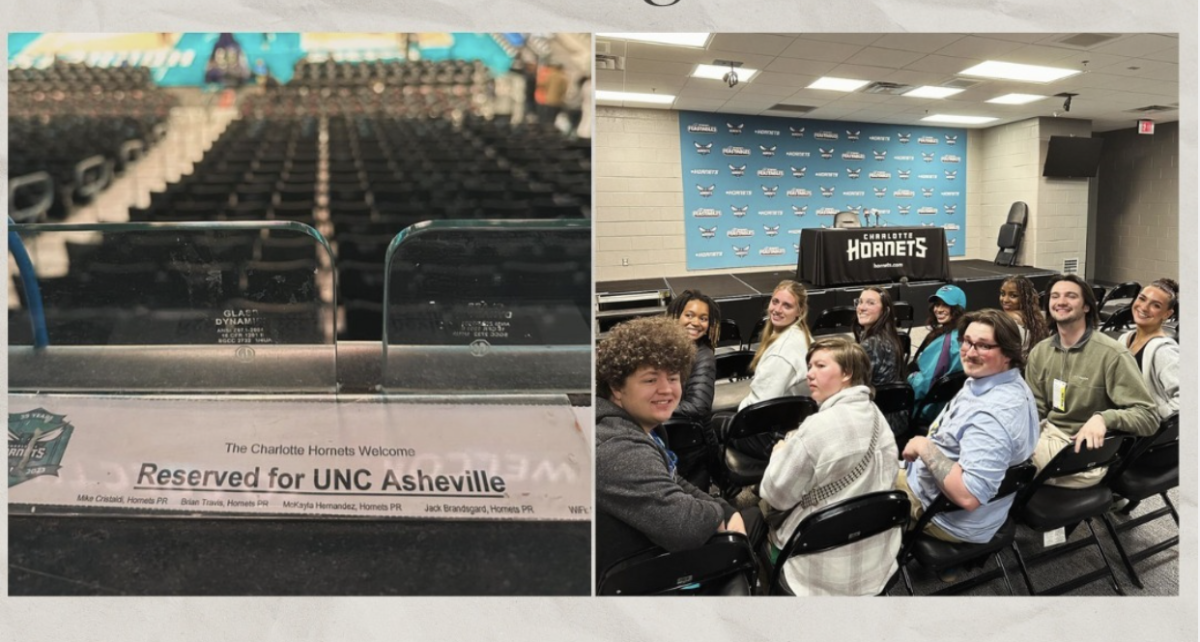

- Mass communication students visit Charlotte to watch Hornets game