by Shanee Simhoni – Staff Writer – [email protected]

America’s health care system can create a divided social structure by providing only certain citizens with quality health care and excluding others, according to professionals in the health care field at UNC Asheville and the surrounding areas.

“It’s a fundamental problem in America, this issue of health care and commercializing health care,” said Oliver Gloag, a visiting associate professor of French at UNCA. “The idea that a hospital has to make money, has to make a profit, is largely absent from the health care arena in France.”

The United State’s health care system ranks 37 out of 191 countries, with France ranking No. 1, according to The World Health Report, a study conducted by the World Health Organization in 2000.

“Across the United States, employers are paying a smaller proportion of employees’ health benefits. Too many people remain uninsured completely and costs of many life-saving medications and procedures are quite difficult for most individuals to finance,” said Brian Nass, the vice president of performance improvement at Mission Hospital in Asheville.

More than 72 million households make less than $25,000 annually in the U.S. Of those 72 million, almost 21 million, or 29 percent, do not have insurance, according to officials with the U.S. Census Bureau.

“I have had uninsured patients pay anywhere from $11 to $300 for a generic prescription, and generally the cheapest one can get a brand name prescription is $50 and can range into the thousands,” said Brianna Reese, a junior at UNCA who works as a pharmacy technician at CVS. “The problem with America’s health care system is that it leaves out the lower-middle class citizens, those who can’t afford quality insurance, but make too much to qualify for Medicaid.”

Between 2002 and 2012, the average family insurance premiums increased 97 percent, from $8,003 to $15,745, but worker’s wages increased only 33 percent, according to Employer Health Benefits, a study conducted in 2012 by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Educational Trust.

“There are so many problems with our health care system that books could be written about them,” said Jay Cutspec, the director of student health and counseling at UNCA. “I don’t think that it creates the social structure, but I believe it is a manifestation of the social structure and results in health disparities amongst social and ethnic classes.”

America’s health care system represents this country’s lack of a balanced distribution of social power, giving too much authority to employers to dictate the appropriate number of sick days, and, as a result, fire employees if they take too much time off to recover from illnesses. In France, a doctor decides how much time an employee can take, as opposed to the employer, said Gloag, who grew up in France.

“Certainly in France, there’s a stronger class consciousness, or at least during the 20th century, a sense of unity amongst members of the working class who got together through parties and through unions to fight for their rights for a host of benefits including the right to affordable health care,” Gloag said.

Fourteen percent of African-American household in the U.S. make an income totaling less than $10,000, which is also the annual income of almost 10 percent of all Hispanic households. The most common annual income for American white households, at almost 13 percent, is between $100,000 and $149,000, according to officials with the U.S. Census Bureau.

“I feel that Medicaid is a success because the lowest class citizens have the opportunity to obtain insurance that, I believe, is better than most middle class citizens,” said Reese. “Patients have few choices concerning doctors, dentists, etc., because many offices do not accept Medicaid.”

America has some of the most advanced medical resources in the world, but only the wealthiest households can afford to utilize them, Gloag said.

“There is a siloed mentality between government, insurers, hospitals and clinics and those companies that produce medications and medical equipment,” said Nass, a health care professional since 2004. “There seems to have not been enough incentive to get all these parties working together to innovate to simultaneously reduce cost to all, improve access and improve outcomes.”

In Asheville, cuts in state funding put a heavy burden on the few institutions that provide services in behavioral health issues, and Asheville’s population, which relies on government-funded insurance more than other parts of the country, has trouble receiving the care needed, because the government does not provide enough money to fully cover the required care and procedures, straining both the residents and institutions, Nass said.

“One specific issue that I’m concerned about locally, in the state, is the decision to not expand Medicaid. This will leave many people unserved or underserved,” Nass said.

The American system does not aim to protect and maintain the health of its citizens, but focuses on the profit earned by insurance and medical companies, Gloag said.

“It’s an issue, I think, of human rights and human dignity, and right now, we’re living our life, all of us, as though it were some sort of lottery, and we’re hoping that we won’t get cancer, we’re hoping that we won’t get sick, and if we do, we’re at the mercy of people who see our illnesses as a source of income,” Gloag said.

Latest Stories

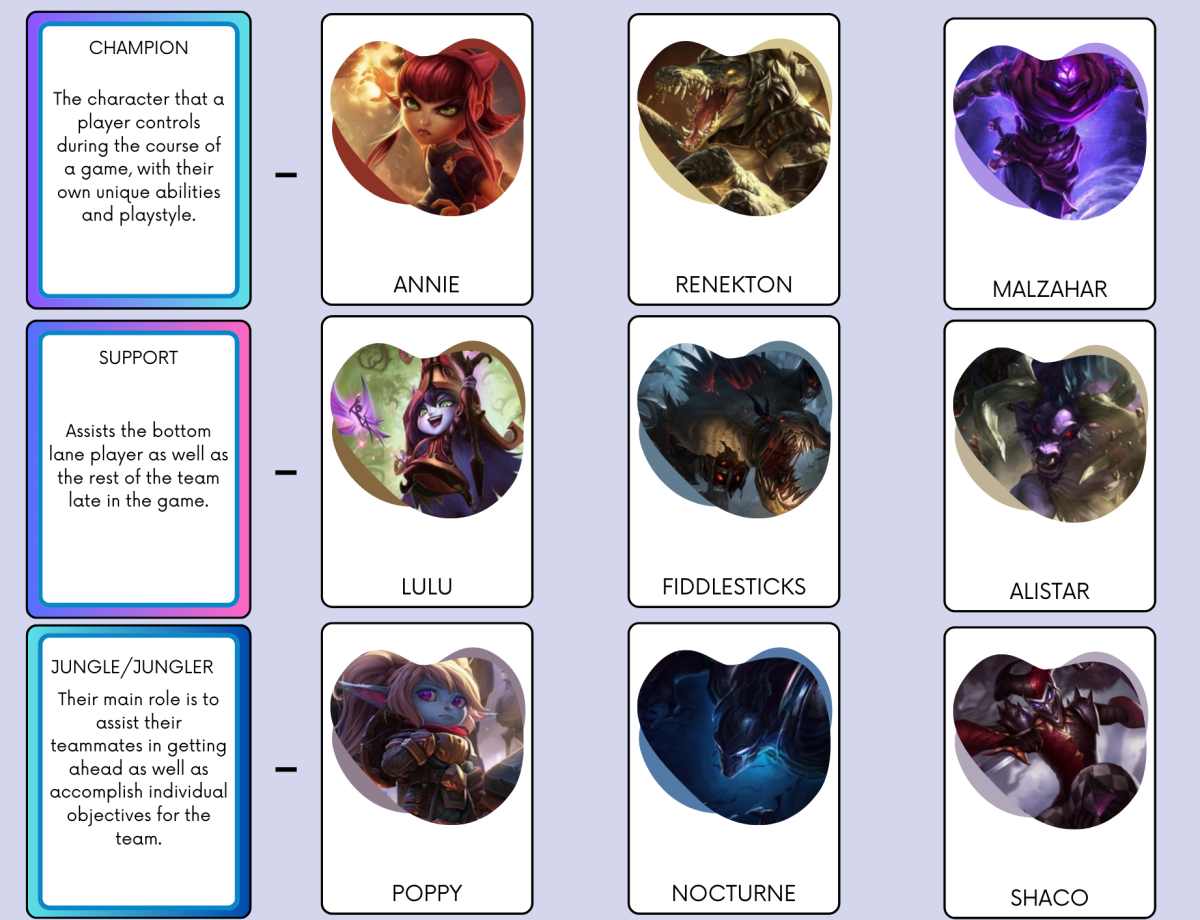

- UNCA League of Legends takes first in stunning finals match against HPU

- From passion to professional play: How a UNCA League of Legends MVP hit their stride

- Old UNCA sorority still has its footprints on campus

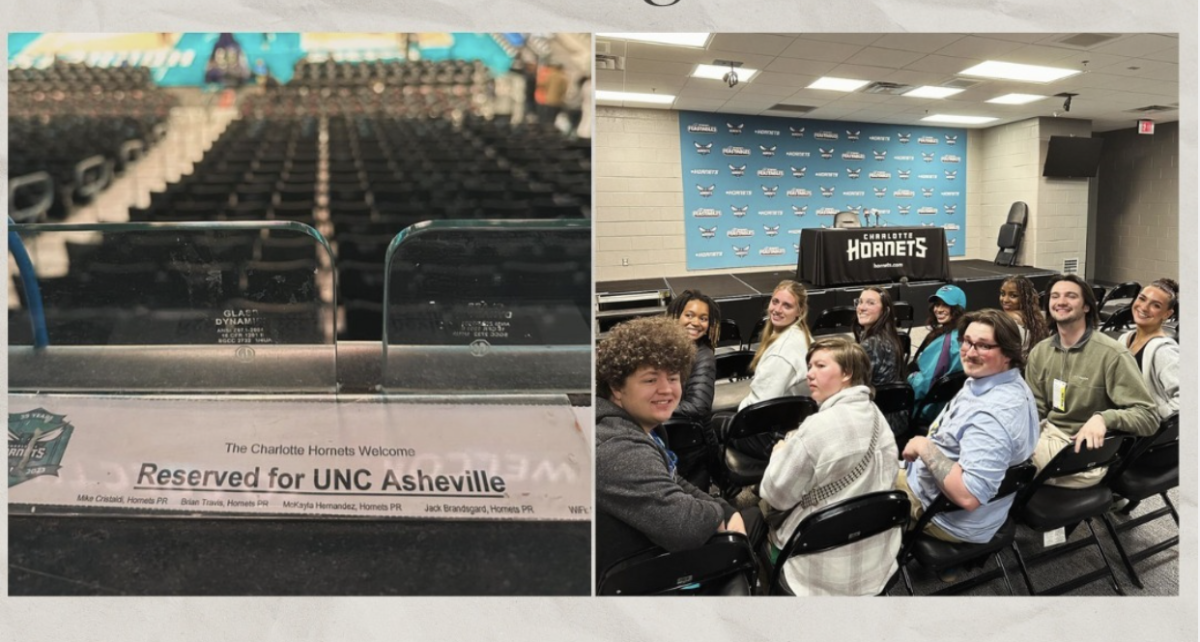

- Mass communication students visit Charlotte to watch Hornets game

- Blue Banner Connections #1

- Sex toys get luckier than traditionalist men

- A student's perspective on traveling and concerts

- Local bead and craft store continues to thrive under new management

- Taylor Swift’s rising stardom causes friction between fans

- Ensuring AI makes appropriate decisions