Bulldogs under surveillance: emails show UNCA monitored students on social media

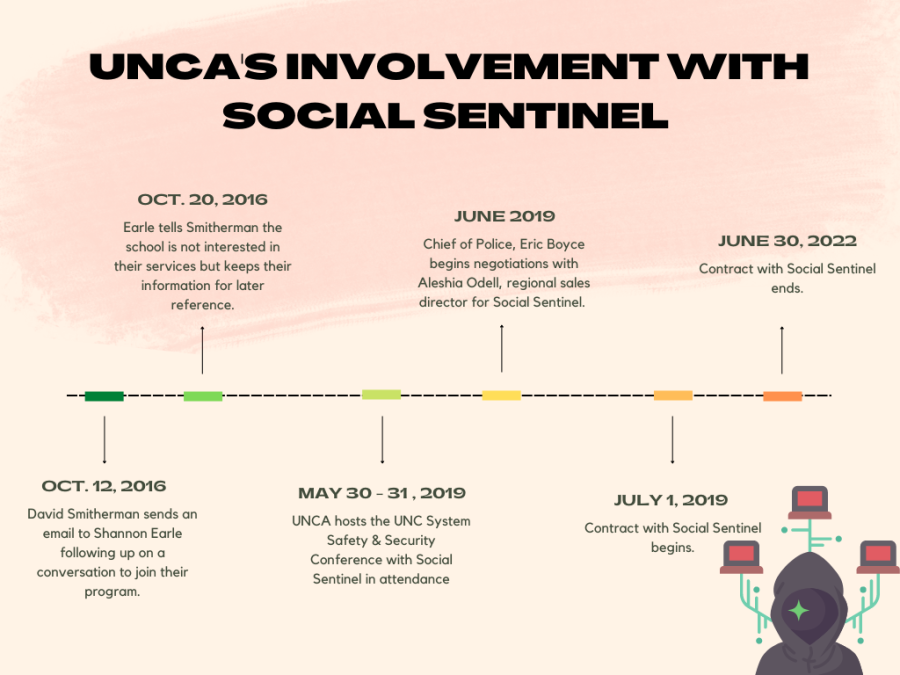

A timeline of UNCA’s conversations with the Social Sentinel program according to public documents.

Public documents show UNC Asheville used an A.I. social media monitoring program, from July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2022. The Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, Meghan Harte Weyant, said the school did not renew the contract.

“I do not intend to renew such a contract moving forward. Additionally, there is no intention to replace it with another service,” Weyant said.

Chief of University Communication and Marketing Micheal Strysick said moving forward, officials at school will continue observing publicly available social media for any worrying or threatening posts. He did not specify who monitored accounts or the number of individuals involved in the process.

“It’s not uncommon that a number of us peek in on Yik Yak throughout the day as well to gain the pulse of the campus,” he said.

Weyant said she uses her Instagram account, @unca_mhw, to build community and connect directly with students. Since she has a social media account, she sees other public accounts and tagged posts.

“My intention with a social media presence is to be more accessible and connected to students as opposed to monitoring. I would encourage students and even faculty and staff to check that profile out because I think it gives a good sense of my goals and interests for using social media to build community,” she said.

In addition to herself and other staff members, Weyant said students and the broader community share worrying posts with university officials.

“I encourage anyone who sees a concerning post that may indicate a threat to self or others to share it with the university directly,” she said.

The beginnings of false promises

Conversations between UNCA and Social Sentinel began in 2019 after a UNC system safety and security conference hosted at the school from May 30 to 31.

The school finalized its contract with the company in June 2019 when the former chief of police, Eric Boyce, signed the contract.

The company initially reached out to UNCA offering its services in 2016, but Shannon Earle, the then chief of staff, declined their offer.

Records show the school spent a total of $31,500 for the three years the school used Social Sentinels services. They paid a total of $10,500 per year, with service fees accounting for $9,800 and data usage fees being $700.

Documents show the school split the cost between four different departments, the dean of students, Highsmith union, university police operations and health and counseling.

According to Jay Cutspec, the director of health and counseling, Boyce brought up the use of the program by other campuses during a student affairs team meeting.

The meeting consisted of old department heads from 2019, like Vice Chancellor Bill Haggard, Dean of Students Jackie Mchargue, Title XI Coordinator Jill Moffitt and Associate Vice Chancellor for student affairs Nancy Yeager.

“At that time, we were really talking more about threats to campus and helping us identify if there were threats to campus,” Cutspec said. “I think we just agreed that all the people who represented those departments would just split the cost. It was sort of a group decision. And I think, to be honest with you, I think Dr. Haggard said, “OK, we’re all just going to split the cost.’”

Several staff members were invited to an onboarding meeting on Jan. 8, 2020. All members of the student affairs team were invited except for Haggard and the addition of Assistant Chief Danny Moss, Lead Telecommunicator Angela Young and Associate Dean of Student Affairs Melanie Fox.

Of all the staff who attended the onboarding meeting, only Cutspec, Yeager, Moss, Young and Fox remain.

Cutspec said he did not use the program but received emailed alerts from the company. He said the program used keywords and could track the location of where posts originated, but when they received alerts, there were no identifying indicators, just the body of text.

“We would click on that, and what we would see would be the message. There would be no information on there. It didn’t serve a purpose because we couldn’t do anything with the information. Because there was nothing identifying them,” he said.

On the Social Sentinel website, their services include the Sentinel Search library, local algorithms and the roles and permissions tool.

According to an email from Dennis Collins, the then regional vice president of sales, sent to Boyce in August 2016, the Sentinel Search library refers to a collection of more than 350,000 threat or harm keywords and behavioral phrases.

An email from Social Sentinel to Boyce shows one of these alerts from Oct. 5, 2020, and shows zero alerts received, one less than the week before and 5,791 associated posts.

After some emails from the program, Cutspec said he stopped looking at the alerts entirely due to their lack of identifiable information.

“It was really purposeless. And so after the first month, I didn’t even look at the messages anymore,” he said.

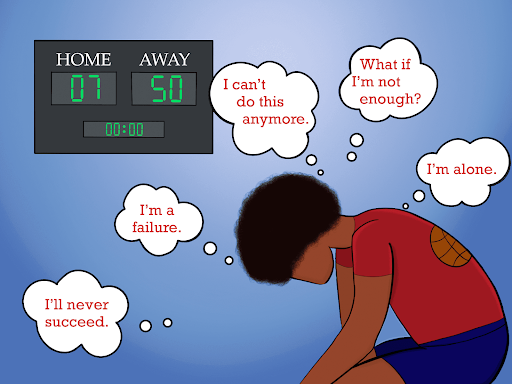

During one instance, when Cutspec decided to check on an emailed alert, he saw a post with someone having suicidal thoughts and decided to pursue it. Ultimately he found no identifiable information besides the social media platform the post originated.

“I tried to see if I could get any specific information about who it was, where it was,” he said.

After speaking with other staff members who received alerts, Cutspec said they came to the same conclusion.

“I talked to Melanie Fox about it, and she had the same experience. It just provided you a post, essentially, with no identifying information,” he said. “There virtually was no benefit that we got from it.”

Cutspec said the program exemplifies entrepreneurship.

“People know campuses feel at risk for a variety of reasons. And so they might say, ‘let’s develop an app that’s sort of going to meet this need or feed into the fear of college campuses.’ And I think this is an example of that which proved to not be very helpful,” he said.

From a health and counseling perspective, Cutspec said the mixing of student safety and privacy comes when one threatens others or indicates self-harm.

“That’s sort of where some of the privacy issues get blurred, and you have to think about it,” he said.

Additionally, Cutspec said students catch posts of suicidal nature faster than any program.

“Everybody is pretty on top of that on a college campus,” he said.

Bulldog reaction to student surveillance

Miracle Okoro, the vice president of the student government association, said student safety requires transparency from officials.

“I think you can say all you want that you’re keeping students safe, but if students don’t know how you’re keeping them safe, we’re not going to feel safe. And I think that’s something the university could do better on,” she said.

Regarding the school’s use of a social media monitoring system, Okoro said she was not surprised as staff often ask about things that appear on Yik Yak, UNCAANON, or other public anonymous sharing posts.

“Something about it seems kind of funny to me if you’re saying that this is for student safety when student safety is actually at risk, why not address that,” she said. “Why not be like, ‘hey we’re surveilling you guys for student safety, and it sounds like somebody’s safety is at risk.’”

Okoro said she does not know the program’s cost but finds the decision to spy on students under the guise of safety as strange.

“I don’t know how much it’s supposed to cost to spy on your students, but personally, if I’m saying I want to keep students safe, my first response would not be to go spy on the students,” she said.

Before joining student government, Okoro had her ways of thinking about certain issues, but after joining, she found herself in a space where she could ask questions and gain clarification.

Although she knows more now, she said students should not have to be in a certain position or association to gain access to information.

“People shouldn’t have to be in SGA to get a better understanding. We should know because we pay to be here. We should already know,” she said. “That doesn’t seem fair.”

Okoro said she understands there are circumstances like legal concerns that prevent the administration from sharing information about student safety but said there are other options they can give students.

“Even if it’s just, ‘Oh ya, this is public record, here’s where you can find it.’ Students should not assume that they do not have access to that information. It should be clearly known that we have a right to that information,” she said. “I’m not them, so I can’t say I understand, but I will say, looking from the outside and seeing how it was reported, it does look kind of suspicious.”

Okoro said it is time for the university to make institutional changes.

“There’s a lot of stuff that has been in place before a lot of us got here, institutionally, that has just compounded probably over the past year or two,” she said. “The university needs to realize this isn’t just certain incidents that burst out of nowhere. These are structural, institutional things that need to be changed.”

To help increase campus safety, Okoro said the student government plans on increasing student representation in the senate as they lack representation for different student employees.

“SGA representation the past couple years or so hasn’t been all that great, and so we can say, ‘we’re gonna create a space for more representation, but if nobody steps up to represent, then there’s only so much we that we can do,” she said.