Food has costly consequences: What happens to our excess food

November 16, 2022

As inflation raises the cost of food it becomes more and more difficult for people in rural areas, in and around Asheville, to access food for themselves and their families. Unfortunately, local nonprofit programs can not serve everyone in the community and hunger persists in more rural areas of Western North Carolina.

“The last numbers I saw from the North Carolina Department of Human Health Services, Buncombe County had a food insecurity rate of 19.6%,” said Jacqueline Hamstead, interim co-director of sustainability for UNC Asheville. “In surrounding counties, a lot of them are even higher.”

Community action:

Marisha MacMorran, the executive director of the local nonprofit organization Food Connection, said in rural Western North Carolina the food insecurity rate increases as the population decreases. This means that even though there are less mouths to feed, it is still hard for some people to feed their families.

MacMorran grew up in rural Pennsylvania working in her family’s restaurant. Living in a rural area, she saw the struggles of those dealing with poverty and food insecurity.

“On Thanksgiving and Christmas we would partner with social services and the department of homeless services, who identified those in need. Before we would celebrate our own family holidays, we would all come together and pack meals to load in our cars and drive out to the far reaches of rural Pennsylvania,” MacMorran said.

According to MacMorran, these people lived in isolated areas and dealt with transportation barriers in addition to food access barriers. Transportation barriers make it even harder for struggling families to access food because even if they can afford it, they may not have the means to access it.

“I was probably 8 or 9 years old when I really witnessed poverty for the first time,” MacMorran said. “Folks living without electricity, who had dirt floors in their homes.”

Now using her business background and over 20 years of experience in the food service industry, MacMorran has the skills and knowledge to help people in similar situations she saw during her childhood through Food Connection.

Addressing food waste:

While working as an operations manager for Celine, a catering company that services events throughout western North Carolina, MacMorran saw plenty of food waste.

“The caliber of clientele we serve in this high-end event industry were wealthy,” MacMorran said. “The wealth disparity becomes really apparent.”

When serving high end clients MacMorran said the worst thing you can do during a catering event is be under-stocked.

When feeding a set amount of people, having enough food so that the first person and the last person to order their meals are presented with the same options requires careful attention and preparation.

“You cannot run out of chicken at a $20,000 catering event for a high-end wedding,” MacMorran said. “So naturally there is food left over.”

Hamstead said in Buncombe county over 57,000 tons of food goes to waste every year.

“We have kept 165 tons of food out of the Buncombe county landfill,” MacMorran said.

UNCA’s dining contractor, Chartwells, has stricter standards for food safety than the state or the federal government.

“The state says this food is safe to eat but Chartwells says it doesn’t meet our standards,” Hamstead said. “When food falls between that window, it actually gets donated and stays locally in the Asheville area.”

According to Hamstead, UNCA’s dining program recognizes that food waste increases costs for them while the excess food goes straight into a landfill.

“Food is cost,” MacMorran said. “I know there are people in our community that do not have enough to eat.”

To combat this, UNCA makes food donations to Food Connection and other local nonprofit organizations that better the community rather than throw them away.

“Coordinating efforts with all of these different groups doing awesome things in Asheville and everybody taking personal responsibility are two good action items,” Hamstead said.

According to Hamstead, Brown dining hall uses 8-inch diameter plates because that prevents people from piling a bunch of food on that they will not be able to eat. The dining hall also offers half portions for those who might not finish their whole plate to prevent food waste.

UNCA’s dining services make sure food avoids going into the landfill, giving peace of mind to the chefs that prepare food in large quantities.

“When given the decision to make 4 pans of rice for an event or 5 pans, a chef will almost certainly choose 5 pans. They know we will come and get it and it will go somewhere that can use it.”

The numbers behind food insecurity:

Data gathered by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics affirms that as of August 2022, the U.S. city average in consumer price index for all urban consumers rose 11.4% since February.

“In Buncombe County, 29% of those experiencing food insecurity do not qualify for food assistance,” MacMorran said.

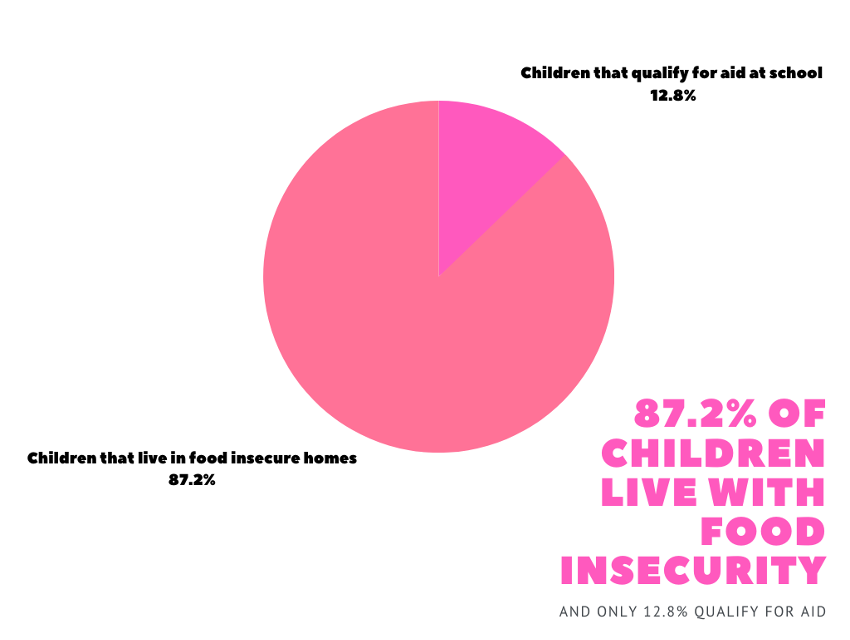

Data gathered by the Southeastern University Consortium on Hunger, Poverty and Nutrition reveals that in Buncombe County, 21.8% of children live in food insecure homes and only 3.2% of those children are eligible for free or reduced-price school meals.

Compared to data acquired by the United States Census Bureau, which shows that Buncombe County has roughly 48,605 registered inhabitants under the age of 18, revealing that even children need help accessing food.

The importance of nutrition and self-sufficiency:

According to MacMorran, the nutritional value of food carries even more importance for children. However for some providers, as inflation raises the cost of food, acquiring nutritious food for their children becomes more and more difficult.

“When looking at families who are stretching their food dollars, they often turn to the dollar store or the fast-food dollar menu because it is a cheap, quick and easy way to feed their children after working two jobs,” MacMorran said.

Findings from the Centers for Disease Control, based on data gathered from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, from 2013 to 2016, 36.6% of adults consume fast food on a given day. If parents consume these non-nutritious foods then so do their children.

To combat the rising consumption of non-nutritious fast foods, middle school conflict resolution, legacy and agriculture teacher at the Woodson Branch Nature School in Marshall, North Carolina, Dana Nagle, teaches her students the importance of agriculture, community and cooperation with one another.

“The mission statement of the school is to grow healthier communities by providing the most effective childhood education through physically engaging lessons and ample time in nature,” Nagle said. “By the time the students leave here after eighth grade, they know how to raise food on a garden level scale. They can do that themselves.”

The school allows students to take home whatever they grow to share with their families. For some families in rural Western North Carolina, this access to fresh produce makes a world of difference.

Nagle said hands-on autonomy and the ability for students to make decisions about what they want to grow, encourages them to eat more diversely and explore what foods nature has to offer.

“They are literally growing their own food, in class, here at school,” Nagle said. “It gives them a sense of empowerment.”