By Brooke Randle

Contributor

[email protected]

For nine years, Scott Walters made his weekly drive to Avery-Mitchell Correctional Institution, a mid-security prison tucked away on the outskirts of the sleepy mountain town of Spruce Pine.

Barbed wire-topped fences and ominous-looking watch towers stood forebodingly as he made his way toward the prison each week. But behind the armed guards and the cold prison walls, Walters saw something different: a classroom.

“When you go into your class the first time, you’re pretty nervous,” Walters said. “After the first night, I was like, ‘This is the best thing ever.’”

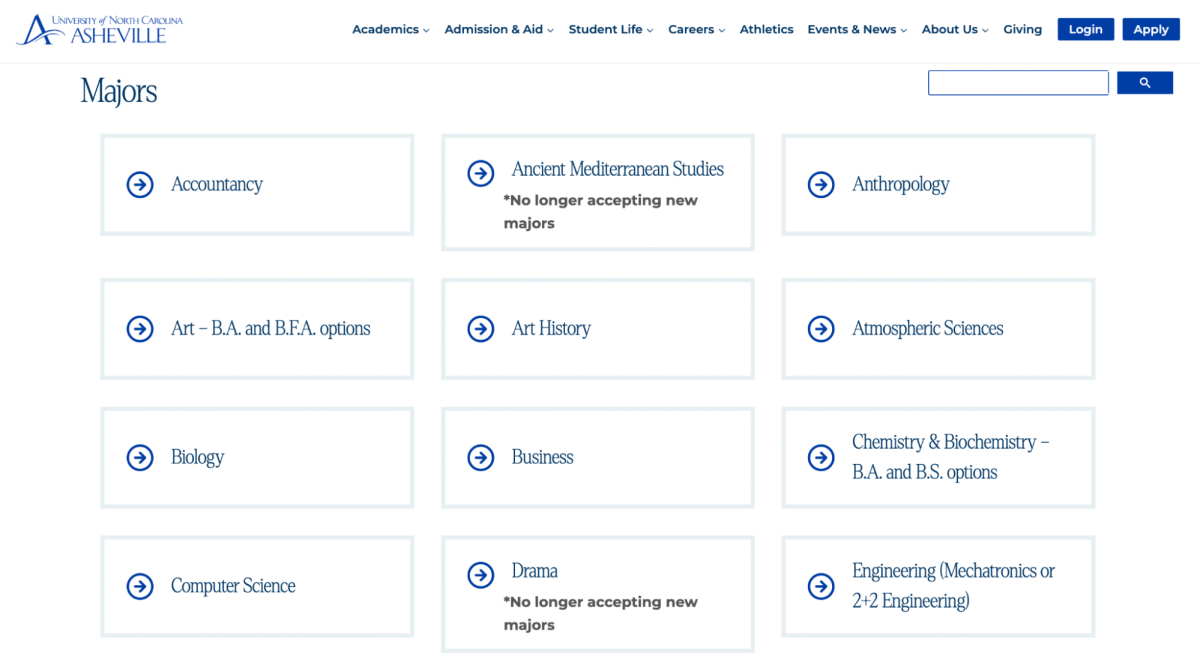

Walters, professor of drama at UNC Asheville since 1998, now leads a group of motivated UNCA professors and administrators who intend to reinstate a program which would provide college-level courses to inmates across western North Carolina. Walters said the program aims to supply inmates with skills and education which may produce a better chance of finding work after serving time.

“We make it very difficult for anyone who has been an inmate to come out and return to any kind of life at all,” Walters said. “We are trying to create at least a handful of people who are not going to bounce back into prison again.”

Education among state prison populations lags behind national standards. According to a 2014 RAND report, only 14 percent of state prison inmates had at least some postsecondary education, compared to 51 percent of the general adult population. As the demand for higher education grows among employers, many newly released inmates find themselves without the necessary skills to find jobs in today’s workforce.

Regine Criser, assistant professor of German, became involved in prison education by volunteering with the Education Justice Project, one of the nation’s leading prison education programs, while studying at the University of Illinois. In the program, she taught inmates courses on American literature, examining works such as To Kill a Mockingbird, Native Son and Catch-22.

“It was super interesting to discuss these major foundational texts with this specific U.S. population who had very strong feelings and insights,” Criser said.

Part of the benefits of prison education programs lies in lowering the rates of recidivism, or the cycle of former inmates returning to prison once more, Criser said.

“We know if we start working with students on the inside with regard to giving them transferable college credit, the recidivism is so immensely reduced,” Criser said. “It makes all the sense instead of continuing to set people up for failure or not giving them the chance to not fail. Why would we not do that? That was something that motivated me in the beginning to be like, ‘Yes, I want to do this work.’”

Professor of Mathematics and Honors Director Patrick Bahls said UNCA’s involvement in prison education reflects the responsibility of the college to the community.

“I think our role as a university, especially as a public university, is at least to serve the community of which we’re a part,” Bahls said. “Because the knowledge, the skills, the ideas that we have here on campus are meaningless and useless if they aren’t applied.”

Bahls emphasized the classes provided by the upcoming program would demand the same level of effort and commitment as those offered at UNCA, rather than skill-based or trade-based courses.

“These are not just classes in prison. These are bona fide classes. These are honest-to-goodness college classes that are as rigorous and important and respectable as any others,” Bahls said.

Despite the outreach from university faculty to bring college education inside prison walls, some faculty members worry about the scrutiny former inmates may encounter from university admissions policies after their release.

About 66 percent of colleges, including all UNC system schools, require criminal justice information during their application process, reports a 2010 study from the Center for Community Alternatives, an incarceration and policy advocacy group.

Dean of Students Jackie McHargue belongs to a panel of administrators and faculty which reviews applicants with criminal backgrounds. McHargue emphasized how her team thoroughly evaluates each application on a case by case basis and has no hard, fast rule for denying or admitting students with past criminal convictions.

“We really do believe in that opportunity to not be defined by a single moment. I think we have to normally weigh what that means, but I think we’re also not a campus that does flat denials. I think everyone deserves a shot at hope,” McHargue said. “And we know education’s life changing. And so we take that responsibility really seriously.”

Senior Director of Admissions and Financial Aid Steve McKellips said he and others who review potential students plan to work with the incoming program to provide former inmates with a fair chance of admission.

“From what I have heard about it, our interpretation of the process falls directly in line with the way that they are trying to get the academic side,” McKellips said. “In terms of what courses, what structure, I don’t have any idea how those things are set up. But I do know that their intent is consistent with the way that we handle the applicants through this process. So, there’s a nice synergy to what the students can be told will happen and what actually happens.”

Currently, the program remains in its preliminary stages of development, Walters said. Although funding remains a roadblock to providing credit bearing classes, Walters said he and other faculty members feel enthusiastic and ready to get started as early as spring 2018.

“We don’t have funding for what we’re doing right now, so I just volunteered to do next semester,” Walters said. “It’s not going to be a credit-bearing class. Normally, they would get three credits just like a regular college class that they could transfer to any institution that they wanted to transfer to. But we wanted to get going.”

Meanwhile, Criser said the response from administrative leaders at UNCA has been encouraging.

“Provost Urgo has been very supportive. He has had higher education in prison programs on two previous campuses that he was involved in,” Criser said. “It’s really nice to be able to do this work with an administration that says, ‘Yes, we want you to do this work.’”

Criser said she and others on campus hold high hopes for the program and look forward to helping rebuild the lives of current and former inmates.

“It doesn’t always work out. We know that. But, the times it works out and the times we successfully reduce recidivism and the times that prison education and support outside has turned former convicts into law students, I mean, it happens,” Criser said. “So, I think we should do that work definitely. Definitely.”

Categories:

UNCA aims to provide education to inmates

September 26, 2017

0

More to Discover