The lecture

“If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game.”

Those were the words of Leonard Cohen as his song “You Want It Darker” filled the Lipinsky Auditorium. As it played students slowly filed in and sat down in the creaking chairs, waiting for the Humanities 324 lecture to begin.

“There’s no more crucial problem than this: we have to consider where we stand with respect to modernity,” said Duane Davis, professor of philosophy at UNC Asheville. “Where modernity is going to be considered an existential condition, that is, modernity is a style of being, a way of existing in the world. Are we modern now? Is that the way we want to be?”

Students coughed, sneezed and sniffled, their echoes resonating throughout the auditorium. Hardly anyone sat shoulder to shoulder, leaving spaces of three to four chairs between each student.

“What is it to be modern?” Davis said. “In the modern age, what have we become? The answer to such questions forms a narrative and this course is establishing that narrative, or a variety of narratives, because each one of us (instructors) takes it in a little different direction in each section. But you (students) have to make the narrative.”

Three-fourths of the auditorium was empty and students half-heartedly listened to Davis’ words, either opting to write down brief notes or to do work for other classes.

Regardless, Davis stood perched upon the podium, speaking of such names as Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Buber, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. All existentialists. All men and women who wrote on the experiences of the individual facing modernity.

Philosophy was not the only thing Davis spoke on. Halfway through the lecture discussion verged from existentialism and modernity to the struggles against power and authority.

“We struggle in the shadows of authority,” Davis said. “Our emails must now be vetted by the Office of the Chancellor. Bureaucratic forms, the rows in this auditorium, the numbers on our identification cards, the machines that own us and operate us without a license, all of this attests to the long dark shadows of authority in which we struggle. Why is it so hard to make time to care for one another amidst our institutional obligations? There are some who don’t know, there are some who don’t want to know, and there are some who don’t want you to know.”

At the word “chancellor” all ears in the auditorium pricked up. Fingers were no longer typing on computers and no one was coughing. All was silent.

“Let’s dwell upon this authority,” Davis said. “Our university is under siege. I believe it’s a political attack – I believe – designed to do away with our public arts institution.”

Financial paradox

The financial crisis at UNCA has been a cause for much concern in relation to liberal arts education. The cutting of budgets and the subsequent altering of adjunct instructors has roused debate among students and instructors, leaving many with questions over the future of the institution.

“There will definitely be downsides and repercussions with the adjuncts, but I don’t think it will be a complete cutting-off of adjuncts,” said Nathan Evans, music technology and philosophy double major at UNCA. “The administration is probably aware of the adjunct situation in the music department, and it’ll be resolved somehow.”

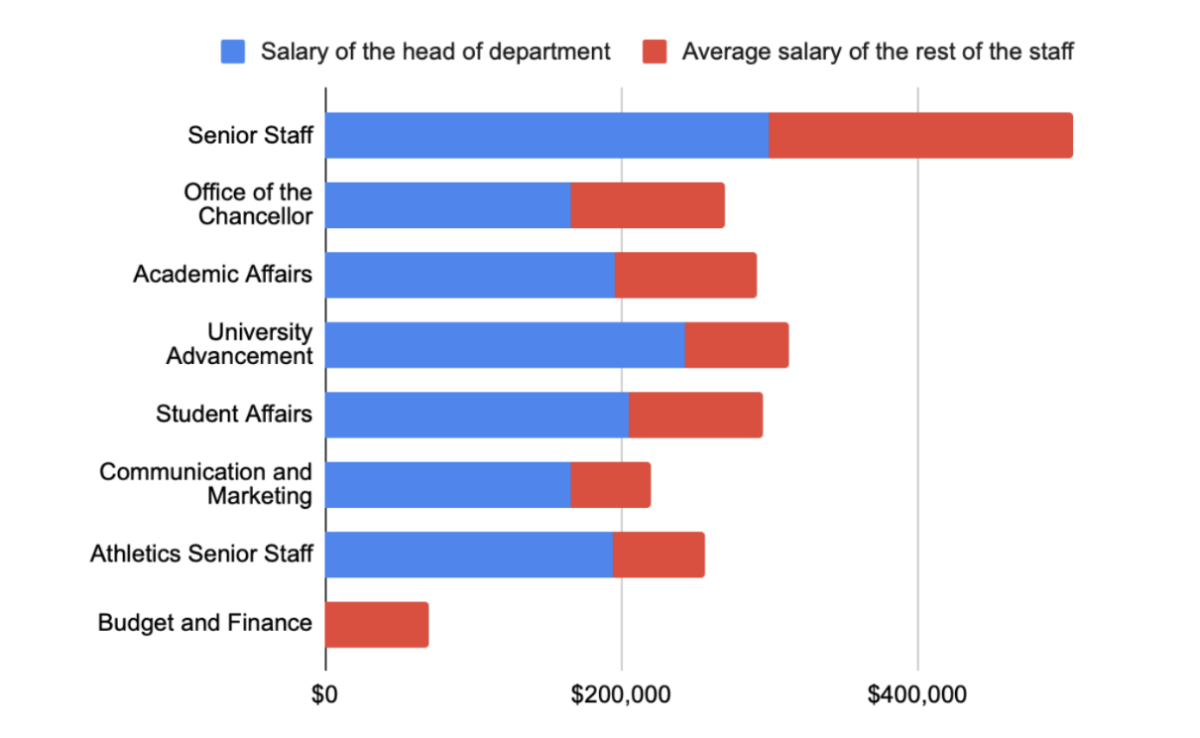

According to the UNC Salary Information Database, senior staff at UNCA have an average salary of $204,761, which is 83% more than the average salary of those within a smaller department such as the philosophy department. Chancellor Kimberly van Noort’s salary currently stands at $300,000.

“I feel concerned about the philosophy program,” Evans said. “I’ve heard from professors that the program might be considered for some sort of mitigation, and I fear for what might happen to the school after that.”

Kirk Swenson, vice chancellor for university advancement, has a salary 110% larger than the rest of the University Advancement staff.

“Funding for professorial research brings prestige to the school,” Evans said. “Professors research so they can write books or papers, and the more professors are able to do that seriously, the more attention UNCA gets.”

Meghan Harte Weyant, vice chancellor for student affairs, has a salary 78% larger than the average salary of the rest of the Student Affairs staff.

“It makes sense that people high in administration make a certain amount more than others, but when the margin is so high, it makes you wonder how the current cuts we’re making are really changing anything,” Evans said. “Who’s making the real sacrifices?”

Michael Strysick, chief university communication and marketing officer, has a salary 102% larger than the average salary of the rest of the Communication and Marketing staff.

“I’m definitely skeptical about the values we supposedly hold,” said Evans. “If liberal arts are not being valued, then UNCA has lost its most important feature.”

Janet Cone, senior administrator for university enterprises and athletics director, has a salary 103% larger than the average salary of the rest of the athletics senior staff.

“I feel as though the direction the school is going is losing what I came here for,” Evans said. “However, I don’t want to leave the school because students and professors still have those values.”

Greg Lovins, interim vice chancellor for budget and finance, is a director at First Tryon Advisors, a company contracted by UNCA. First Tryon Advisors is paid a monthly fee from UNCA, and Lovins is part of that contract.

“If it comes to it, I’ll go down with this ship,” Evans said.

Transforming identity

Professor Davis’ lecture came just two days after the UNC Board of Governors Committee on University Governance voted unanimously to reverse and replace the UNC System’s diversity, equity, and inclusion policy. The full Board of Governors will make a final decision in May.

“It couldn’t be more explicitly bigoted,” Davis said as he sat in his office, his circular glasses resting venerably upon his face and his gray hair showing his years. “You can’t make this stuff up.”

Davis, who was at one time the head of the budget committee for the UNC System Faculty Assembly, said he learned more about the system than he wanted to know. This position granted him a perspective and understanding that now allows him to speak against some of their methods.

“Plato, in the Republic, talks about how some music is dangerous, and it’s a long story as to what I think he’s really doing with that. People take it very literally, but he seems to be banning certain subjects from instruction. I know he’s saying there’s some dangerous music and there’s always dangerous music such as gangster rap or Elvis Presley hips or whatever,” Davis said, smiling and shaking his hips. “You’re going to go straight to hell if you listen to this kind of music.”

Of course, Davis was joking, but there was real concern in his words. If education can be controlled in a way that limits the learning of certain disciplines, what then becomes of those disciplines and histories?

Davis said geisteswissenschaft, a 19th-century German term, means the study of the human spirit, spirit science or human science. The term covers both the humanities and social sciences and may today be associated with the liberal arts.

“Everything was philosophy, right?” Davis said. “Chemistry, biology, all that stuff. Even into the 18th century, if you were going to study those things you would describe to people that you were studying natural philosophy, you know. And then those disciplines became isolated.”

The seven liberal arts from ancient times to the medieval period consisted of the trivium of rhetoric, grammar and logic, and the quadrivium of astronomy, arithmetic, geometry and music. Over the past few centuries, as the sciences became more isolated from the humanities and society began to face modernity, a great concern over vocational education arose, and what followed was the false association of liberal arts with modern liberal politics.

“There’s nothing more conservative pedagogically than liberal arts,” Davis said. “And in fact it’s been used to systematically exclude these (marginalized) people. Only the elite could have that kind of educational environment. We’re not teaching the quadrivium and the trivium, you know, it’s a metaphor for small classes, intimate interactions of faculty and students on and off campus. People don’t understand what the word liberal in liberal arts means. It means to emancipate, to free us to be the best people we could be.”

While teaching at another institution, Davis said he was the sponsor of the philosophy club. To ensure the emancipation of the mind, they had a T-shirt that said to question all authority, and on the front, it listed out different forms of authority, but down at the bottom, it said Dr. Davis.

In delivering his Humanities 324 lecture, Davis was questioning authority and speaking out against it, and while there were worries over what would happen following the lecture, he decided that what he was doing was much more important than what could happen to him.

“Younger faculty, their jobs are on the line and they don’t want to speak out,” Davis said. “Senior faculty who have tenure are more protected, but in this kind of environment where they declare a financial hardship, they can do whatever they want to do, you know, they can get rid of anybody.”

Davis’ voice was shaky, his emotions permeating every word.

“The threat isn’t to my job or any one person’s job, the threat is a generation of people who don’t have the opportunity to think critically,” Davis said, sorrow in his soul. “The problems that we can’t even predict, your generation is going to have to deal with, largely because of my generation. Things are going to change a lot in the next two generations.”

For students and staff like Davis, there is little to respond to publicly. While the releasing of staff and the freezing of funds may evoke outcry, changes in programs cannot yet be protested simply because they have not come to pass, but among students and staff, there is a constant feeling of impending doom surrounding the future and which programs may be kept, merged with others, or outright cut.

“I hope students will make it known to people paying for the education, whether it’s families, institutions, scholarships and things, that they’re not getting what they’re promised,” Davis said.

What the hell are liberal arts?

The term “liberal arts” has a complicated history. In a general sense, this type of education may be primarily associated with the arts and humanities, and little else. However, this would be a wrong assumption.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, liberal arts are described as “College or university studies (such as language, philosophy, literature, and abstract science) intended to provide chiefly general knowledge and to develop general intellectual capacities.”

This definition helps, but there are still holes. Language, philosophy and literature are obviously liberal arts, yet abstract sciences are somewhat different. In contemporary times, abstract sciences may just be associated with natural and formal sciences.

“The idea of a liberal arts education is a broad education as opposed to a narrow education,” said Reid Chapman, interim director of the humanities program at UNCA. “There are a lot of schools with a lot of programs where you take the vast majority of your coursework in your major. And so you don’t have the opportunity to learn about – unless you’re a history major, unless you’re a literature major, unless you’re an art major – things that might go beyond your own particular, narrow field.”

A liberal arts education focuses on a general study of the sciences, the social sciences, the arts, and humanities. Despite this modern consensus, liberal arts education still exists in a gray area.

According to UNCA enrollment statistics in the spring of 2024, 43% of the student population are seeking a Bachelor of Arts Degree, while 27% are undeclared and the remainder are pursuing a Bachelor of Science Degree.

Not every Bachelor of Science Degree program at UNCA would be considered a liberal art in the traditional sense, but as the meaning of the term changed, so did its programs.

“We have, within the university, three divisions: social sciences, natural sciences and humanities,” Chapman said. “And what has traditionally been within the humanities often has a narrower definition of the liberal arts.”

If the more traditional understanding of liberal arts is applied, 19% of the UNCA student population are seeking degrees in the humanities and arts. This perspective is harmful in understanding what liberal arts are.

“Here in UNCA we’ve really expanded the humanities program to include the social sciences and the natural sciences because that’s also a very important part of the human experience,” Chapman said.

If the current understanding of liberal arts is applied, then 59% of the student population are partaking in the liberal arts according to their major. Makes sense. UNCA is a liberal arts university, but the liberty that can be taken between 19% and 59% is potentially dangerous.

“We had an accreditation visit with the engineering program here on campus, and the folks who came in were really excited to see and thought it was noteworthy that the engineering and mechatronics students here at UNCA had an experience in the humanities program that broadened their narrow field of study,” Chapman said.

According to the American Academy of Arts and Science, an honorary society and independent research center, 3% of humanities majors in North Carolina are unemployed, the same percentage as business majors. In comparison, 2% of natural science and engineering majors are unemployed.

Using these same statistics for North Carolina, the median annual earning of humanities graduates is $63,188, while behavioral and social science graduates earn $65,586, a 3.7% difference.

However, the difference between art graduates, $55,882, and natural science graduates, $75,825, is 30%.

Although there is a significant increase in the earnings of arts and natural science graduates, Chapman said UNCA offers a broad range of education no matter what program a student may be in.

“Liberal arts education prepares you for careers that don’t even exist yet,” Chapman said.