A great deal of black history in Western North Carolina went previously unrecorded or ignored, but research committees, storytellers and historians are helping unveil the truth.

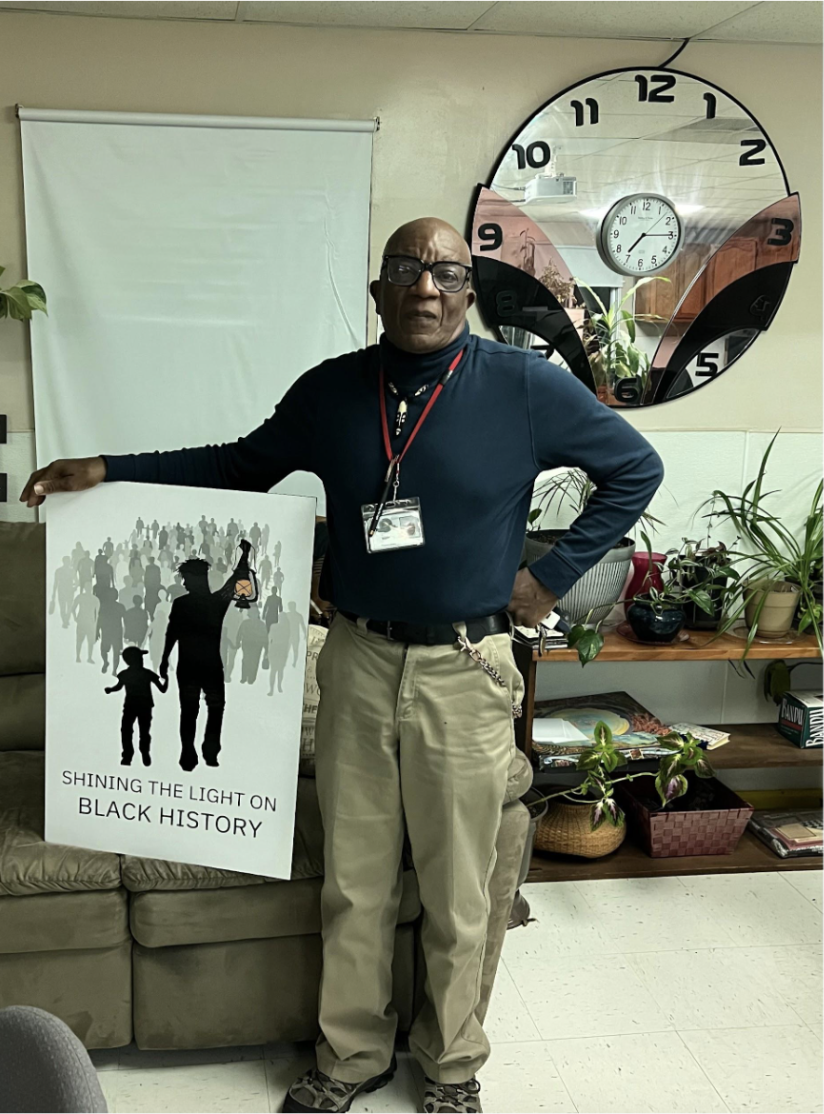

“There’s not going to be any pictures, there’s not going to be a whole lot of writing things down because it was against the law for a slave to write,” said Ronnie Pepper, a librarian, storyteller and president of the Black History Research Committee in Henderson County. “So if we did, we had to do it undercover, and one thing you ain’t going to be doing is keeping those journals of everything you’ve seen and done, because if you get caught they’re going to kill you.”

Pepper said the research committee not only pieces together information from slave documents, but oral storytelling as well.

“If you ain’t documented it, it ain’t been done,” Pepper said. “But we see the value of oral history because we are oral people. When we were in Africa, it wasn’t that we couldn’t write, but we were social people, that was one of our characteristics. We liked to come together as a group and talk and listen through song and dance, so that was a positive thing, but some people don’t see that as positive.”

During slavery, Pepper said singing brought hope and kept many slaves alive, and Pepper wants to pass that strength on to other generations.

“I tell stories of growing up, family stories, stories that I have learned from different cultures and whatnot because storytelling is in just about every culture and every race there is,” Pepper said. “It’s about good, it’s about evil, it’s about being right, it’s about forgiveness. Those are the basic things in every culture.”

Pepper said Sadie Smathers Patton, a white woman, first documented a local story, “The Kingdom of the Happy Land,” in 1957. The story takes place during the reconstruction era and is based on truth, but because of scant documentation, little is known about the definite extent of the story.

“Her story was that slaves came, after they were free, from Mississippi off of a plantation and their leader was probably, from her description, a man who could pass as white and he received education from his white father,” Pepper said. “They ended up in the foothills of North Carolina down in Green River, so that was from her story and there’s some truth in it.”

Pepper said the group of freed slaves established a community by pooling their money together and buying property in the area, and in doing this they were much safer and they could provide a living for themselves and their families.

“So individuals came up, they used the skills that they had used from slavery, which they didn’t learn from slavery because when they came enslaved from Africa they might not have had clothes, but they had a language which was taken away, and they had skills,” Pepper said.

After the Smathers Patton book resurfaced, Pepper said he began to question the legitimacy of her version of the story. According to him, a lot of the story did not make logical sense, and once the committee started doing further research they found a lot of the people in the kingdom came from Cross Anchor, South Carolina.

“We found articles and papers and things that said these people were fanatics, that they were cannibals, that they ate their own, that they were murderers, and people were already this discouraging,” Pepper said.

According to Pepper, Robert Montgomery led the kingdom and they bought land from Serepta Merritt Davis, a former slave owner. Part of the property was in North Carolina while the other part was in South Carolina.

“The farm was already there, the blacks were just able to re-establish it,” Pepper said. “So instead of them being slaves, they could work it and get paid, and so they hired themselves out to people in the community and around the area and earned money.”

According to Pepper, the railroad and the closing of a Zircon mine on the property put many people in the kingdom out of work, and because towns such as Hendersonville were growing, many sought opportunities elsewhere.

“There’s a lot of individuals that we’ve been calling invisible footprints,” Pepper said. “The footprints are there but you just don’t see them, but they were just as important. If we can tell these stories, then it changes the way children look at people of color. And my thing is I ain’t standing out and waving a banner or marching, I’m just going to tell the story because there’s a lot of folks that will listen.”

According to Sarah Judson, a professor and the chair of the history department at UNC Asheville, oral history and documented history offer different insights, and without both, history cannot be told effectively.

“Deeds or bank documents or the meeting minutes of an organization, those give you insights into what has happened right on the ground, like kind of a material basis for history,” Judson said. “Oral histories can offer different perspectives about how people are viewing reality, so these things are really important, but they’re not the same.”

Judson said oral tradition is a long-standing way people pass stories down from generation to generation, and because Southern society at one point did not welcome the documentation of black history, communities extensively used oral history.

“It would be potentially problematic to only rely on an oral tradition on stories that have been handed down because we might not know if those things really happened,” Judson said.

According to Judson, because historians have not documented something does not mean oral history should be discounted. She said if an event went undocumented, a historian, student or scholar could use old newspapers and the register of deeds as a foundation to build documented history.

“If someone wanted to find more information about a group of people, a great place to start would be in the cemeteries and looking at the names and doing genealogical research,” Judson said.

According to Judson, marginalized people are oftentimes documented in relation to more powerful people.

“History, in general, is a devalued subject, so when you start dividing it into minoritized groups, that (history) in the larger public seems to have less and less value, but it really should be the opposite, because people should have access to not only their history, but the history of the people that they’re in community with,” Judson said.

According to Carissa Pfeiffer, a librarian at the Buncombe County Special Collections, archival collections contain primary sources such as documents, photographs, maps, letters, diaries and audiovisual materials.

“As primary sources, archival collections are the building blocks that historians, whether scholars or amateurs, can use and analyze to get a comprehensive understanding of the past,” Pfeiffer said.

According to Pfeiffer, archives and special collections grew out of the need to keep official government records as well as the need to maintain the collections of typically wealthy white men.

“Some black history can be gleaned by reading between the lines when documentation is sparse, like when the white newspaper survives but the black newspaper doesn’t,” Pfeiffer said. “In more recent years there’s certainly been a resurgence in community-driven efforts to document, actively collect, and preserve black history.”

According to Pfeiffer, Buncombe County Special Collections scan photographs, accept donations offering a window into black life and work with community organizations to support them in building a community memory.

“We really encourage individuals, families and communities to be proactive in collecting and documenting their own history so that future researchers will know what was important to us at this point in time,” Pfeiffer said.