Katie Walker

Arts & Features Staff

[email protected]

The temperature in Nepal rose to over 100 degrees, public transportation was down due to strikes. Dehydrated from walking five hours each way to and from a village, David Gillette felt a sense of relief when he reached the main road.

Before making his trip to the village, Gillette forgot to pack iodine drops used to purify the water from hand pumps. By the time he reached the main road back to where he was staying, Gillette felt as if he was going to pass out.

“I remember they were selling bottles of Sprite, I remember distinctly it was so cold it was almost slush,” Gillette said. “I will always remember drinking that Sprite.”

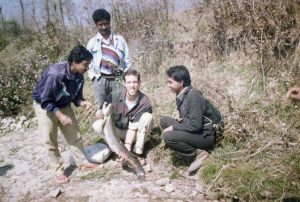

Before coming to UNC Asheville, Gillette traveled to Nepal as a member of the Peace Corps in 1995 and worked to improve fisheries in local villages. He spent two years working with fish farmers and another year evaluating the impact the Peace Corps had on the area.

Gillette was accepted into the environmental studies department at UNCA in fall of 2008 as an associate professor.

Irene Rossell, professor and chair of the department of enviromental studies, said the team who first interviewed Gillette knew right away he was someone they wanted. She remembers interviewing Gillette and thinking he was a great person based on his answers to each question.

“All the questions we asked him, he was very thoughtful, articulate and just gave such great answers to our questions,” Rossell said.

Since coming to work at UNCA, Gillette formed a good relationship with his students and colleagues. Kevin Moorhead, environmental studies professor, said Gillette is a great guy to work with and talk to.

“He is hard to rattle, very level headed and very calm,” Moorhead said. “Because of that calmness, I think that blends well with interaction with students.”

Gillette and Moorhead co-taught a class together three years ago called Environmental Restoration. Because of their overlapping research and fields of study, Gillette being a river expert and Moorhead being a wetland expert, the two worked well together.

After receiving research grants from the Fulbright Foundation, National Geographic and World Wildlife Fund, Gillette returned to Nepal in 2015 to conduct research on the effects of climate change on river systems. The project also looked at information gathered from previous studies conducted in the area during the ‘80s and ‘90s.

The Kali Gandaki River, located in central Nepal, served as the focus of Gillette’s studies. Starting at the Tibetan Plateau, the Kali Gandaki flows down through the Himalayas to northern India.

“What is interesting, is just like the French Broad River here, which was flowing before the Appalachian Mountains rose, that river was flowing before the Himalayas arose,” Gillette said.

Through his research Gillette found the number of species in the river decreased since the last group of researchers gathered data. The rare species of fish in the ‘80s and ‘90s were close to extinction in 2015.

He and his team put more than 40 temperature data loggers in the river and used the data to create a mathematical model. Researchers compared the current river temperature now to historical river temperatures using the data collected.

During his time in Nepal, Gillette worked with local fisheries to increase breeding among fish species. Gillette said his team injected hormones into the heads of fish to increase breeding.

“What we did was extract the pituitary gland from the heads of the fish harvested for eating, then you grind them up in a mortar and pestle, mix them with distilled water, then you suck it up in a syringe and inject it into the fish’s muscle,” Gillette said.

The team went out and injected the fish with the hormones around 4 a.m. When they went to check on the fish a few hours later, the fish had bred. Gillette was shocked at the results, not expecting the treatment would be a success.

One of Gillette’s more memorable moments was when he carried a bag of baby fish from a fishery to a village.

With the plastic bag of fish on his back, Gillette got on his bike and headed toward the village. On the way to drop off the fish, Gillette had to carry his bike across a river. In the time he spent in the village, rain caused the river level to rise past the depth safe for wading across again.

During his time in Nepal, Gillette said he was able to pick up on the culture and language of the area. He learned to work and function in their culture as he would in his culture.

People in the town offered Gillette food, water and shelter until he was able to safely cross the river.

“They offered to make me dinner, these were people who did not have much from a material aspect at all,” Gillette said. “These people were totally willing to share their food, their home and everything with me.”

![Brooke Pedersen [second from the right] and Luis Reyes [right] hold banners during the Wrap The Woods event.](https://thebluebanner.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ELIZABETH_PRITCHITT_IMG_3470-1200x804.jpg)