Ashton Van Dyke

Contributing writer

[email protected]

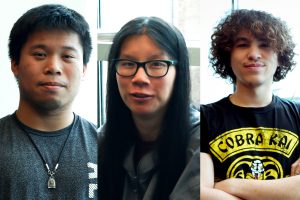

Alex Ear (left), Camaryn Ormond (center) and Adam Wan (right) are members of ASIA club. ASIA stands for Asian Students in Asheville, and its goal is to provide a community while also educating on Asian culture.

When atmospheric science student Alex Ear started at UNC Asheville, his experience did not meet his expectations.

“When I first heard about the school, they were going on about how it’s such a diverse campus,”Ear said. “When I came here it was kind of a let down.”

Ear, who is of Southeast Asian descent, felt underrepresented as an Asian-American student. A 2016 report from College Factual reveals that Asian-American students only make up two percent of UNCA’s student body.

To find a community, Ear decided to join ASIA club after his cousin recommended it.

“He told me, ‘This is the place for you and you should go for it. Give it a chance,’” Ear said. “I took that advice and I think that is the best thing I did since I came here.”

ASIA stands for Asian Students in Asheville. The club provides a space for Asians and their allies to discuss Asian culture and issues the community faces. Club members also bond over crafts, food and simply being with each other.

Though ASIA creates community, club president Adam Wan said there is still work to be done for Asian representation at UNCA.

“There should be more representation of Asian students here, whether that be in passing on the website, in more Blue Banner articles or on more videos that are shared throughout school,” Wan said. “Honestly just seeing more faces that look like mine or seeing more people that resemble me would make me feel better represented, like I belong more to this university.”

According to lecturer of mass communication and media studies scholar Stephanie O’Brien, lack of representation also enforces reductive stereotypes.

“When marginalized groups don’t see themselves and their stories in media their marginalization and the stereotypes perpetuated by certain representations are reinforced,” O’Brien said.

A common stereotype Asian-Americans face is that of the model minority. The model minority narrative states Asians have assimilated into corporate American culture and are thriving in it.

“Crazy Rich Asians,” one of the few pieces of American mainstream media with a predominantly Asian cast, paints a picture of Asians living in decadence. This idea is not unfounded, as according to a 2016 Pew Research Center analysis, rich Asians are the highest-earning group in America.

However, this does not account for income inequality, nor does it paint a picture of the entire group. The same report also indicates that Asians in the top 10th percentile made 10.7 times more than those in the lower 10th percentile.

This difference makes Asian-Americans the most financially divided racial group in the nation. According to a 2018 report from the Asian American Federation, financial mobility for poor Asians has stagnated in the past forty years. In New York City, New York Asians are the poorest immigrant group. This disparity is caused by varying degrees of education, skills and English proficiency.

Coming from an immigrant family, Wan’s experience does not match the model minority narrative.

“When [my uncle and my grandparents] came here they had very little money and very little connections,” Wan said. “They worked in a plant. They got paid very little and the working conditions were not that good. For a while most of their furniture was packing crates and cardboard boxes. It’s really humbling to see that.”

The model minority stereotype harms Asian-Americans by separating them out from conversations on diversity by downplaying any struggles they face.

The model minority stereotype also harms other minorities by drawing a comparison, according to NPR.

By saying Asian-Americans have worked hard to achieve the same financial success as wealthy white Americans, the stereotype places the blame on other minority groups for not working hard enough to achieve the same thing.

“There is no such thing as a model minority,” Wan said. “We shouldn’t be comparing minorities and our struggles.”

The importance of accurate Asian representation has been made more clear with the spike in anti-Asian racism surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak. O’Brien connected historical context to already existing prejudices Asian-Americans face, which have only been exacerbated due to fears surrounding the outbreak.

“Linking a certain country or ethnic group to a pandemic is directly linked to aggression that Asian people continue to face,” O’Brien said. “These links reinforce already existing stereotypes from media and rhetoric surrounding the world wars and trade wars. These links place blame on the ‘other’ for an event that the dominant group cannot grasp.”

According to a CBS news report, high schoolers in San Fernando Valley, California physically assaulted a 16-year-old classmate while accusing him of having the virus. An ABC news report from last month detailed how a man in Midland, Texas stabbed three members of an Asian-American family at a Sam’s Club. Similar the incident in California, the man believed the family was infecting people

From March 19 to April 1, the nonprofit organization Stop AAPI Hate received more than 1,110 self-reported incidents of hate experienced by Asian-Americans. These incidents range from assault to vandalism.

Racist content has proliferated social media. This includes commentary on the viral “bat soup” video, which features Chinese influencer and tourist Mengyeun Weng. The video was taken in 2016 on the Pacific island nation of Palau, not Wuhan. It has no links to the outbreak. Weng has since apologized in a tweet for releasing the video, stating she had no idea it would be associated with the virus.

Though the virus likely originated in bats, bat meat is not a food staple or delicacy in China. Guansheng Ma, the director of Nutrition and Gastronomy at the University of Beijing, clarified this in a press statement.

“Eating bat meat is more than rare in China,” Ma said. “It’s actually unacceptable in Chinese culture.”

Virologists remain unsure as to how the virus first spread to humans. Nevertheless, the viral video has been appropriated to spread misinformation.

International studies student Camaryn Ormond who is Vietnamese-American, recalled a tense moment faced by another member of the Asian community.

“My sister has a friend who is an adoptee,” Ormond said. “She went to the grocery store and was followed around by someone the whole time.”

The surge of racist behaviors toward Asians does not just impact those of Chinese descent.

“She left the store and while on the phone with my sister she said, ‘I’m not even Chinese,’” Ormond said. “Basically looking ‘Chinese’ really hurts others in our community.”

“The Coronavirus has put the blame on the Chinese and that hate has transferred to all Asian-Americans, no matter their ethnicity,” Wan said. “Very few feel safe coughing or sneezing in public because of the multitude of incidents that’ve occurred as a result of the high tensions.”

Despite the scapegoating of Asian-Americans, their concerns about the virus are the same as everyone else: stay inside and stay safe. According to Wan, a combination of visibility and action is key to combating ignorance.

“People can assist the Asian communities right now by making people more aware of how offensive the slurs and jokes that they say are,” Wan said. “People can publicize the violence and graphic events that’ve happened recently against Asian individuals and they can stop the spread of ignorance toward the Asian communities when they see it happening.”

![Brooke Pedersen [second from the right] and Luis Reyes [right] hold banners during the Wrap The Woods event.](https://thebluebanner.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ELIZABETH_PRITCHITT_IMG_3470-1200x804.jpg)