Local therapists push for diversity within their field

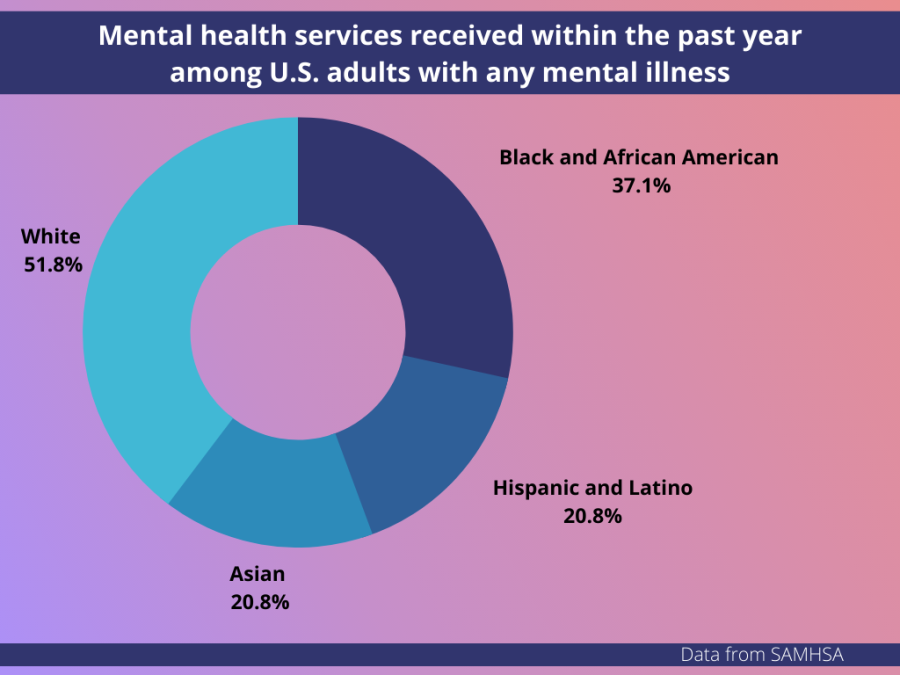

Data from the National Institute of Health breaks down the racial percentage of individuals with any mental illness who received services within the past year.

When it comes to why communities of color do not seek mental health help, Nichole Johnson, a Black therapist in Asheville, said tendencies to pathologize communities of color, a history of medical mistrust and lack of representation get disregarded or simplified.

“These barriers can be used and have been considered as the blame or issues with BIPOC communities receiving access to services, which it shouldn’t be because there are other reasons for that being so and those things are structural,” she said.

Psychology Today, a website focusing on psychology, lists 872 local therapists and professionals in Asheville. Of those listed, 146 have a client focus on one or more ethnicity groups.

Johnson is one of the 146 listed on Psychology Today and operates her private practice, Beginners Mind PLLC, out of her home.

“Majority of the places I have worked in I was the only Black therapist,” she said.

Patients of color seeking a therapist of similar racial background face difficulty as data from the American Psychological Association shows 84.47% of active psychologists in the United States are white.

“They might engage in services and not feel seen, or not feel heard, not feel understood or having to teach their clinicians about their experiences or feeling invalidated,” Johnson said.

According to Johnson, simple things like changing visual representation in advertisements help invite communities of color into therapeutic spaces.

“It can sometimes give the impression that different populations are not welcome or there are just spaces that different populations don’t go to. And so it leaves out the opportunity for people to see themselves in these spaces,” she said.

Data from the National Institute of Health shows that 37.1% of Black and African American people, 35.1% of Hispanic or Latino people and 20.8% of Asian people with any mental illness received mental health services within the past year.

“BIPOC communities can be seen as these groups of just struggle, instead of a group of play, of an abundance of worth and deserving of consideration and knowledge and equitable support and representation,” Johnson said.

Although therapists have incorporated cultural competency in their practice, Johnson said they must aim for cultural humility by acknowledging their limitations with clients from different cultural backgrounds and recognizing their differences even if they come from the same culture.

“There can be a risk of over-generalizing BIPOC communities,” she said. “Cultural humility allows us to acknowledge the differences while also holding ourselves accountable for seeking understanding.”

For Johnson, humility as a therapist holds utmost importance, respecting a client by asking difficult cultural questions and knowing when to pull from outside resources creates a well-rounded therapist.

“Not doing so disregards a person’s experience and in this society that does have structural oppression embedded within it, it impacts everyone,” she said.

Accessibility and culture, blockades on the path to wellness

Accessibility to services remains a top priority for Johnson as she accepts both insurance and offers a sliding scale. For her, the lack of access for communities of color often gets shadowed by cultural differences.

“There has been research showing the biggest barrier to BIPOC communities seeking mental health services is actually cost and access to health care,” she said.

Accepting insurance or sliding scale fees results in less financial income for the therapist causing some to overload on clients.

“They might end up burned out because they’re seeing more clients, but their finances might not be as representative and so that can lead to therapist burnout,” she said.

Johnson said the difficulties of obtaining affordable health care and the lack of choices add to the need for mental health help.

“Feeling like there are not many options. Going back to feeling oppressed and just having to deal with things as they are, not feeling like there is an abundance, not feeling like there are enough people they can go to and get to decide who they want to work with from various backgrounds,” she said.

A Therapist Like Me, a non-profit organization that helps connect people of color with therapists of similar racial backgrounds, aims to help make services sustainable for both clients and therapists of color.

“Clinicians of color are able to get their full reimbursement rate which helps them and their business so that they can continue to be sustainable. When they are not sustainable then they do not have their practice or they might end up burned out,” Johnson said.

Ashley Hosey, another Black therapist in Asheville with her own private practice, said the addition of telehealth helps increase accessibility.

“Were able to reach communities that we weren’t able to at first,” she said. “Our approach to therapy is a lot more accessible.”

Hosey said not knowing the symptoms of mental health issues contributes to the hesitancy some people of color have when seeking help.

“Going off on people, tummy aches, feeling stress in their shoulders. A lot of those BIPOC clients can not name that,” she said.

In communities where spirituality holds importance, Hosey said for those seeking therapy, the importance of prayer pushes them into isolation.

“You have that guilt of disappointing your family, then disappointing my religion and my culture and my identity. And it just stacks on top of each other, and it’s just, it’s overwhelming for people,” she said.

For Hosey, the importance of having a therapist of the same racial background helps with client vulnerability, as some therapists avoid conversations regarding racism.

“If we are scared to talk about police brutality, if we are scared to talk about racism then that client does not need to see you because we are doing more harm than good. We want the client to say, ‘I am scared and I am comfortable saying I am scared in this space,’ because they are used to masking that fear,” she said.

Hosey said white therapists working with clients of color must be comfortable being uncomfortable.

“Something to you that may seem perfectly normal is really a huge stressor for somebody else. Being able to say, ‘I may not understand it, but help me, explain the process of that fear, even though I may not ever feel that way,’” she said.

Besides access to resources and culture, Johnson said the role of structural systems within a person’s environment gets overshadowed by a fixation on behaviors.

Johnson said another cultural difference relates to how structural racism and oppression affect communities of color. According to her, those structures may not be considerations for why symptoms present.

“That’s embedded in our systems and it can have an impact on a person’s life experiences. Even daily life experiences,” she said.

The way others perceive the expression of mental health symptoms in communities of color also holds importance as Johnson said some are viewed criminally.

“It’s not always viewed as people having mental health symptoms, or having challenges or people trying to function in a society of disparities,” she said. “People’s suffering gets overlooked and ignored and disregarded, when there is help, there is support out there.”

This criminalization also applies to children, as according to Johnson, a child’s environment and other psychological issues get shadowed by disruptive behaviors.

“It might be a response from anxiety or depression or trauma, in that these other significant mental health areas are not being in effect and just the behaviors are just being looked at,” she said

Medical mistrusts impacts on communities of color

Jessica Casimir, a sociologist at UNC Asheville who studies the effects of intergenerational trauma within the African diaspora, said the definitions within the DSM-5 do not account for differences in how cultures express mental illness, especially suicidality.

“The definition of suicidality is also very narrow because it doesn’t really incorporate other forms of suicide that are outside of a significant life-ending event,” she said. “I am a firm believer that people do commit suicide in other ways through various self-destructive behaviors that will eventually lead to death. This can be done consciously and unconsciously.”

From 1845 to 1849, James Marion Sims conducted gynecological experiments on enslaved African women. Due to Sims’s use of enslaved African women, controversies arose over consent and the ethics of his work.

“All the trauma and history has basically resulted in this distrust,” Casimir said.

Although most studies look at the physical effects of intergenerational trauma, Casimir said mental health risks for post-traumatic stress disorder increase.

“It fails to account for a lot of these stressors that can impact the stress hormone being impeded into your bloodstream and how it affects your physiological chemistry,” she said

Casimir said fears of documentation and mistrust of health care officials root themselves in communities of color due to medical experimentation and manipulation.

“The idea of reporting and having things documented can be a very big trigger in the sense of once things are initially documented it’s recorded and can this work against me?” she said.

Depending on the severity of a patient’s description a provider might deem it necessary to send a patient to a psychiatric hospital and for Casimir, this act can cause more harm to a patient.

“That is typically very unethical, not being aware of what additional harm that response could take,” she said.

When it comes to the treatment and examination of mental health issues, Casimir said professionals must look at social structures affecting people of color rather than the individual.

“Obviously agency does exist, but at the same time agency is very nuanced. It works on a spectrum. People have only so much ability to make certain choices,” she said.