On Wednesday, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill went into lockdown for the second time in a month for gun activity on campus.

“You don’t believe it will happen at your school until it does,” said Weslyn Hall, a 19-year-old Psychology senior at UNC.

Mickel Deonte Harris, a 27-year-old Durham resident, waved a gun inside a bagel shop on the UNC campus, forcing the university into lockdown only two weeks after the fatal shooting in late August. The deadly shooting, carried out by Tailei Qi, a 34-year-old doctoral student, took the life of Zijie Yan, an associate professor at UNC.

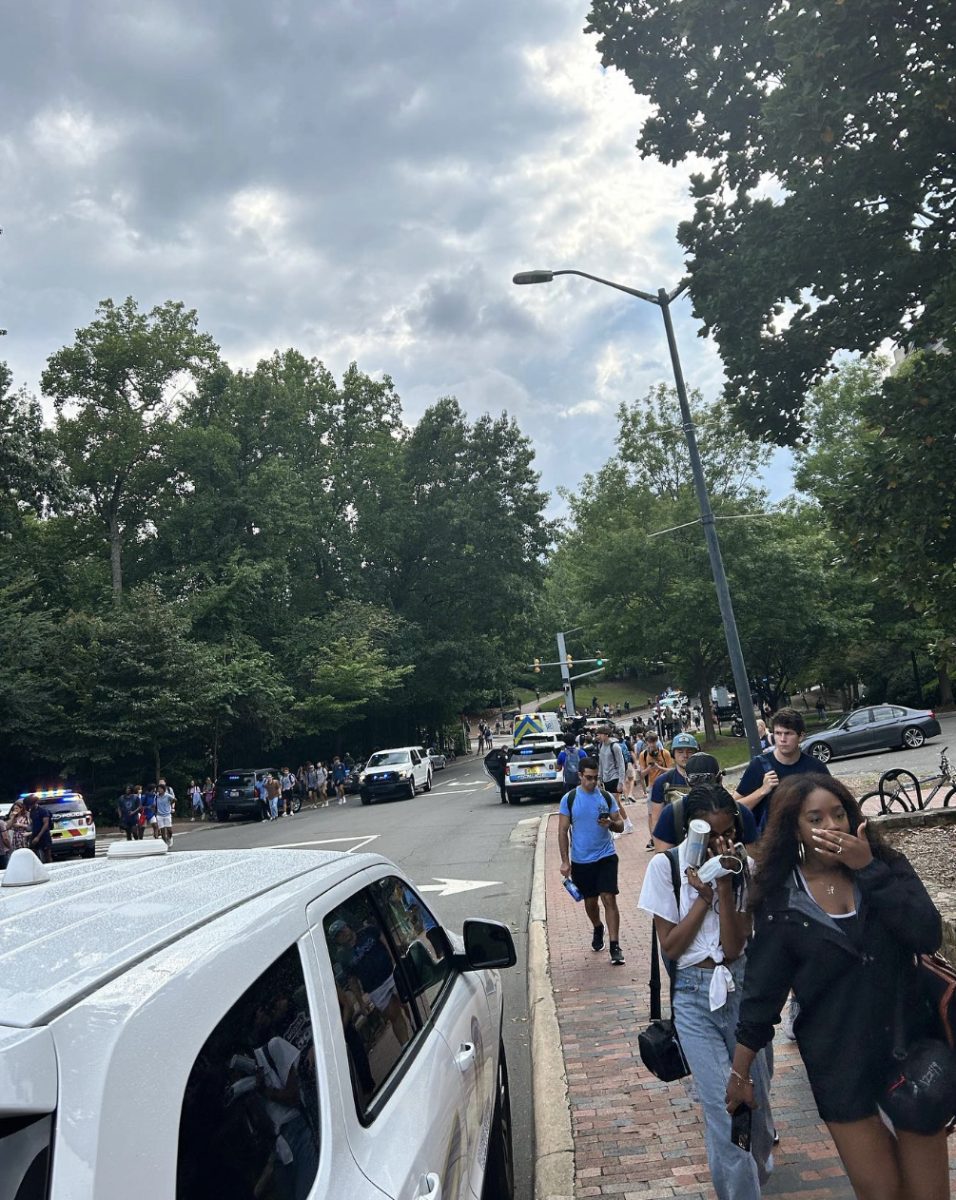

Photo courtesy of Weslyn Hall, Psychology senior at UNC Chapel Hill. (Weslyn Hall)

“Looking around, I noticed no one seemed to be panicking or moving very quickly. It was like my brain couldn’t register what was happening, and based on the reactions of those around me, that seemed to be a shared experience,” Hall said.

Hall said the lockdown on Aug. 28 was three hours long, and the uncertainty of the event was the worst part of the experience.

“We were all in shock, wondering why and grieving the loss of a member of our community. I learned it took place two buildings over from the building I was in for the entirety of the lockdown,” Hall said. “I cried, knowing that this day that started out like any other could end in tragedy.”

Blu Buchanan, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Asheville with a doctorate in feminism theory and research, teaches a sociology of violence course this semester.

“We got to talking about the stuff after the UNC news. I was like, OK, students think faculty, for example, are more prepared than we are. I don’t know what to do in an active shooter situation,” Buchanan said. “We are not prepared in any way for it.”

Buchanan said the faculty is only shown a run, hide, fight video and given fire extinguisher training.

“We are not prepared as a campus to adequately respond,” Buchanan said. “When the emergency preparedness guy is like oh, it’s fine for me to pull out a toy gun and point it in your face. Without realizing it’s not just a story of active shooters. There are people who are coming into our university that have been in those situations.”

Last fall, student employees were given active shooter training in Highsmith Student Union, in which the student hub remained actively open to passersby who were unaware of the meeting.

“UNCA has gone the surveillance route. I don’t think students realize there is a system in place for professors and other folks to report them and be like this is a concerning student, and that activates a whole network,” Buchanan said.

According to Jemima Malote, the former editor-in-chief of The Blue Banner, the meeting involved showing videos of past shootings and drills where students were to run and hide from an imaginary gunman.

“The surveillance is framed as care, making it seem we are this good campus providing wrap-around services and not actually addressing the fact that it is underlying forces like white supremacy and toxic masculinity that are really the foundations of gun violence,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan said professors are asked about participation. Students struggling are most likely disabled or BIPOC, even though most shooters are white men. They said the system that is watching for struggling students will not catch the person who is most likely to be the shooter because white men are seen as more capable than BIPOC students by default.

“We’ve witnessed it twice in the span of three weeks. I am afraid of the fact that nothing is being done about the issue,” Hall said. “We are tired of having to face the fear that something could happen again. We want change. We want stricter gun laws. We want more security. We want to feel safe on campus.”

On Aug. 30 and Sept. 12, the UNC Young Democrats held rallies demanding change from lawmakers.

“They went to the North Carolina General Assembly and chanted ‘vote them out’, during the assembly. They were escorted out, but not before getting their message across,” Hall said. “We want our voices heard and we want change.”

Hall said she was in the med school’s dining hall, a portion of campus she had never been to before when a friend texted her asking her if she was OK.

“I didn’t know what they meant, but before I could ask, an alert notification came to my phone,” Hall said.

The alert sent to UNC students, faculty and staff read, Alert Carolina Emergency: Police report an ARMED AND DANGEROUS PERSON ON OR NEAR CAMPUS.

“I was with my roommate and neither of us knew what to do,” Hall said. “We ran out of the dining hall, lined with windows, into another building nearby. We found a study room without windows and hunkered down with a few other people.”

Hall said some unaware students continued to eat lunch. Once the news spread, the dining hall cleared out quickly. UNC faculty workers were diligently corralling students to safety into nearby buildings.

“I felt almost desensitized. Of course, it’s a serious thing, but we just went through it,” Hall said. “If anything, it has just made the issue of gun violence feel so much more real. We all knew it was an issue, but it’s dawning on all of us that it’s so easy for someone to get a gun onto campus.”

Diamond Forde, a third-year English professor at UNCA with a doctorate in African American poetics and fat studies, said part of the problem with gun violence in the United States comes from culture and availability.

“If we aren’t thinking about education. If we aren’t thinking about giving classes on how women can protect themselves. If we aren’t also on the flip side actively working with men and teaching them about other options for protection and stripping the connections away between toxic masculinity and gun culture. If we aren’t taking that kind of multi-faceted approach it is just going to keep perpetuating,” Forde said.

Forde said it is easy to look at other countries and see how successful they are at banning guns. However, there will not be a straightforward solution until the root causes of white supremacy and toxic gun culture are dismantled.

“When I am talking about a culture around guns I am mainly just talking about white patriarchy and white supremacy. Our strategies we are going to have to use to uproot our attachment to guns in this country is going to have to be uniquely American,” Forde said.

Forde said universities need more critical race theory, and denying access to these theories only further the goal of white supremacy. She said ideologies like hood feminism and intersectional approaches to feminism remind people gun violence disproportionately affects black women, and learning from these theories is a way to get in front of the pervasiveness of gun violence on campuses.

“The problem is fear is such an irrational force. How do you dismantle fear when fear is probably the thing that makes us all human? That fear has been probably the greatest motivator for change and unfortunately some of that change hasn’t always been positive,” Forde said. “We are ultimately brushing against fear.”

Forde said one of the things that feminism is going to have to brush up against is perceptions of safety because the thing people hear when talking about retaining gun rights is fear.

“After Sandy Hook I was not comfortable in school. Even as a kid. As an 8-year-old, I didn’t really know why I was doing this but I was looking at exits, I was looking at windows, I was looking at where the closest makeshift weapon was,” said Carwyn Schumann, a 20-year-old student at AB Tech.

Schumann said America is so heavily involved with firearms it’s not as simple as taking them away or regulating them.

“Stereotypes and generalizations are such a hard thing to talk about with gun control. You go 50 miles, and people have guns for very, very different reasons,” Schumann said. “Some people live in areas where having a gun is necessary to survive and protect yourself. More than anything, I think people fail to see that those two things can be similar. Is feeding your family not protecting them?”

Schumann said if someone chooses to own a weapon, it should be kept in a gun safe, the ammunition should be held separately and the code should only be known by adults with the legal ability to operate firearms safely.

“I do support the ownership of handguns for self defense and home defense and hunting weapons, but outside of that I think the American population has far too much access to deadly force,” Schumann said.

Schumann said a fundamental part of American culture is the expectation of men to own guns and have a weapon to protect their wives and kids.

“My grandfather has a collection, not of weapons I would consider irrational to own but he has multiple hunting rifles, he has a shotgun. He has handguns,” Schumann said. “He worked his way up in the business world in the ’60s that is a part of his accomplishment. Look at my beautiful house, look at my beautiful wife, Look at my gun I protect those things with. It is just part of the property mentality in America. The gun is property and it is also insurance for other property.”

Schumann said a good example of how to look at gun culture in the United States is to look at old cigarette ads.

“If you are told everyone is doing it, you need to try it, you need to have it. Even if it is pitching something that inevitably kills people. You gotta have it. You gotta try it. Everybody’s got one. Obviously you don’t see commercials on prime time talking about, get your gun today. It is that instilled belief my neighbor has a gun and this person I don’t know has a gun, what if either of these people come into my home,” Schumann said

Buchanan said one of the primary motives of the shooter from the Charleston church shooting in 2015 was the shooter felt black men were stealing white women from him.

“Not because white women are people but because they are taking away something that is mine and if we had more white women then I would have a few for myself being able to then garner status and respect from other men,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan said the idea of standing your ground is based on defending your property, including women as a part of said property.

“The idea that a man’s home is his castle means he has the right to act however he wants on his own private property. What is interesting is those same protections have seeped out of the home into the public space,” Buchanan said. “I’m at a gas station and a Black person is playing their music too loud and they don’t listen when I say that I want them to stop so I shoot them. All of that is about the way the Castle Doctrine in the US is used to justify violence both legally and socially.”

Buchanan said the Castle Doctrine in North Carolina, also known as standing your ground, is rooted in slavery and settler colonial genocide.

“With gun violence in communities it is simply an extension. It is saying I want more of this space to be my space and I will claim it at the end of a gun,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan said if someone wants to take someone out with another type of weapon, it will happen. They said it is about harm reduction and breaking down the societal expectations of toxic masculinity to rip the problem out by the roots.

“If we as a society have a consensus that it should not be easy to get a gun. Is that going to stop somebody from getting a gun? Maybe not, but what it does say is, we have decided that we don’t want to see this and stigmatizes it as a source of solutions for a person,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan said society has a neoliberal understanding of gun violence, making for a weak set of tools to address gun violence on campus.

“If I am just pruning off a few leaves from the top that will help in keeping the problem from getting any worse but that is not stopping the thing from growing,” Buchanan said. “We start with our relationships and we find ways to not rely on systems that are violent. When we show we don’t need those systems of violence those systems will respond with more violence and that can be a revolutionary moment.”

Buchanan said something small like first aid kits in the classrooms or making it free for faculty to get first aid training would show the university is more prepared to care for the community.

“They should be advocating for their students and on behalf of their students to see things like changes in gun laws. Universities can’t stay silent about it and they also can’t continue to treat it as one offs,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan and Forde said universities need to take student opinion seriously to create a successful system.

“I think the students now, even more than my generation, have been disproportionately affected by gun violence and the prevalence of it within their schools, if anyone knows on the ground level what it is like to live with these fears,” Forde said. “If we are not taking the opportunity to listen to our students to evaluate and to incorporate measures to make them feel heard on campus we are doing them a great disservice.”

Hall said she thinks a lot more now about what could happen, finding herself whipping her head around to find the source of loud noises.

“Everything finally began to feel as normal as it could, for me at least, until someone else brought a gun on campus. When will we be able to rest and not worry about being harmed in the place we call home,” Hall said.