Maggie Haddock

News Staff Writer

[email protected]

Participation in political advocacy increased recently, stemming from mobilizing events such as the Women’s March on Washington and the Moral March on Raleigh.

On March 1, citizen lobbyists gathered in Raleigh to speak to their representatives about gerrymandering, honing an exponential number of participants, according to Jen Jones, communications director for Democracy North Carolina.

“The energy is high here in North Carolina for advocacy at this point. Normally, this type of redistricting Lobby Day gets 60 or 80 people. There were 600 to 800 people there,” Jones said. “The energy you’re seeing at moral march and the women’s march is spilling over to what’s happening at the general assembly right now and also what’s happening at board of elections meetings and city council meetings.”

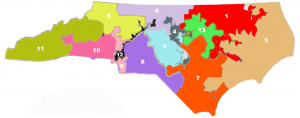

The successful Lobby Day took place to address gerrymandering, the redrawing of districts in order to manipulate election results.

“It’s the strategic drawing of districts to advantage some party,” said Ashley Moraguez, assistant professor of political science at UNC Asheville. “It is when some people draw lines for districts, whether it be for congressional districts or state legislative districts, to make some advantage toward one side or the other.”

Partisan gerrymandering, the act of redistricting in favor of political parties, proves to be condemned less frequently than racial gerrymandering, redistricting in order to isolate racial groups.

Sydney Nazloo, a sophomore political science student, discussed redistricting in its affirmative and negative aspects.

“The idea of racial gerrymandering when you use it to exclude large groups of minorities and disperse them along congressional districts so they have less voting power, that’s definitely an issue because it means that they’re being, essentially, disenfranchised and breaking that one person, one vote doctrine from Baker v. Carr,” Nazloo said.

Although racial gerrymandering isolates minority groups, Nazloo argues there must be some redistricting in order to balance the skewed placement of minorities.

“The Voting Rights Act actually stipulates that there should be majority-minority districts and that there needs to be in order to re-enfranchise previously discriminated-against groups,” Nazloo said. “Striking a balance between that is difficult, striking a balance between really enfranchising minority voters and completely disenfranchising them.”

Non-profit organizations such as Democracy North Carolina and Common Cause held Lobby Day training sessions in order to train citizen lobbyists how to speak to their representatives about gerrymandering.

Darlene Azarmi, a Democracy North Carolina organizer for Western North Carolina, said persistence in lobbying builds relationships with legislators.

“Getting to know those leaders and building relationships by showing up to talk or call or write somebody three times versus one time or 12 times or 72 times versus never, that is relationship building that, inevitably, in some capacity will pay off,” Azarmi said.

Compared to paid lobbying where experts on a certain topic or policy speak to political actors, citizen lobbyists typically carry influence if enough people show up to lobby, Moraguez said.

“Citizen lobbying can be effective if it happens in large enough numbers. One citizen lobbyist is probably not enough to actually much of an impact, but if a group of citizens lobby for something, you’re hitting legislators or any political actor where it hurts the most, which is their electoral vulnerability,” Moraguez said.

The success of Lobby Day strengthens the already growing movements of citizen activism, Moraguez said.

“I do think that right now, we’re seeing more grassroots activism than we have in a very long time, where your average citizen is actively getting involved and is trying to put pressure on their elected officials,” Moraguez said. “We saw a little bit of this during Obama’s presidency where the Tea Party movement was really, really active and they got people to go to town halls and advocate, but it wasn’t on the scale that it is today.”

Non-partisan organizations such as Democracy North Carolina continue to encourage advocacy, insisting citizen involvement manifests change, according to Jones.

“It’s incredibly important that people get involved now, and there seem to be endless opportunities to do so,” Jones said.