Kathryn Devoe

News Staff Writer

[email protected]

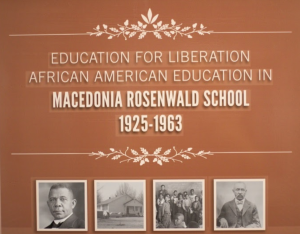

The Macedonia Rosenwald School opened its doors in 1925 as a place of education for black children in the Batesville, Mississippi community until the school closed in 1963.

Cheryl Johnson, an alumna of both the Macedonia Rosenwald School and UNC Asheville, created the exhibit Education is Liberation to document the history and story of the Macedonia school.

“It became clear to me that it was important to excavate the story, to document the story, present the story and to tell the story because as I was doing my research, one of the quotes that I came across that was really inspiring to me was, ‘Many people have tried to tell our story, and have done so poorly,'” Johnson said. “I thought we should be telling our own story and I can tell this little small story about this small community and this small school where I got my primary education. I can tell that story.”

The idea of the Rosenwald schools originated from Booker T. Washington and the exhibit opened on his birthday, April 5. He saw the need for a better primary and secondary education system in the South for black children, according to the exhibit located in Zagier Hall.

There were 5,000 Rosenwald schools total and the schools served one-third of black children in the South by 1928, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Johnson started the journey of collecting information about the Macedonia school by contacting alumni.

“I began to contact alumni that were still alive, all over the country,” Johnson said. “I would identify one person there to be my coordinator. They were in touch with all the alumni who lived in their city.”

The people who attended the Macedonia school tended to keep in touch, Johnson said.

“Even though those people left that community, they took the community with them,” Johnson said. “They maintained that community in the city of Chicago.”

The alumni of the Macedonia school helped provide photographs, quotes and information for the exhibit.

“From 1925 when the school first opened, I was able to find a photograph of the first teacher,” Johnson said. “His family still lives in the community.”

Deborah Miles, director of the center for diversity education, helped coordinate the exhibit and talked about the greater impact of it.

“What she (Johnson) did to bring that community together, the exhibit is an example of that,” Miles said.”The power of the relationships, the pride of that community, the love.”

Western North Carolina also had Rosenwald schools which served the community. Oralene Simmons and Anita White attended local Rosenwald schools and discussed their experiences at the exhibit opening.

Simmons attended the Anderson Rosenwald School in Mars Hill, which opened in 1929.

“I remember I walked a long way to the bus stop to catch the bus that would take me to the Rosenwald school,” Simmons said. “It was a bus that originated out of Marshall, took the students there and also picked up students from Hot Springs who had made the trip to Mars Hill by train.”

Simmons also shared the conditions of the school.

“In addition to being a one-room school, it did not have electricity. It did not have indoor plumbing,” Simmons said.

Miles said the location of the exhibit in Zageir seemed fitting because many of the education classes occur there.

“We decided to ask the Department of Education if we could do it there because it’s very much about the education system in the South,” Miles said. “We wanted it to be available to education students.”

Lisa Sarasohn, an attendee of the exhibit and friend of Johnson’s, said she had an interest in the role of Julius Rosenwald helping Booker T. Washington.

“One of the things that interests me is Jewish people being allies for African Americans,” Sarasohn said. “And what I’d like to learn is more about how Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington came together and hatched this idea.”

The Rosenwald schools are named after Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish philanthropist who gave seed money to Booker T. Washington to start the schools.

According to the exhibit, Rosenwald contributed to the schools for the ‘good of mankind.’ He wrote the racial prejudice black communities face resonates with Jewish people because of their past persecution.

Sarasohn said she had a question about what could come of the exhibit.

“I’m wondering what inspiration can come of the story of the Macedonia school that can be brought forth today,” Sarasohn said.

Johnson said schools still remain segregated in less prominent ways by offering classes to white students that are not offered to black students.

“Even those schools that are integrated where black and white students are in the same building, under the same roof going to school, they’re still segregated because they created something called Advanced Placement classes in which they track the white kids into and then they track black kids into regular classes,” Johnson said.

Johnson said people should follow the advice of Nikole Hannah-Jones, an investigative New York Times journalist who spoke about school segregation at UNCA in February, to de-track and desegregate schools.

“There’s no evidence that a white kid sitting next to a black kid learns any less because they’re sitting next to them, which is what white parents seem to be concerned about,” Johnson said.