Karrigan Monk

Editor-in-Chief

[email protected]

In the span of an hour, 23-year-old Orson Welles put the fear of death in more than a million people.

It was the night before Halloween in 1938 and the nation was still reeling from the lasting effects of the Great Depression. Radio was the dominant media form of the era. On the Sunday night of Welles’ broadcast, most Americans tuned into the most popular performer of the time, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen.

When Bergen’s broadcast ended, many listeners turned the dial to CBS where Welles was 12 minutes into his War of the Worlds broadcast, based on the H.G. Wells novel of the same name. Though there was a disclaimer made at the beginning of the broadcast that it was fictional, many listeners missed it by tuning in late.

Of the six million total listeners of the broadcast, approximately 20 percent of these people thought the broadcast was news coverage rather than a fictional Halloween special.

“You have to remember the period this happened,” said Eugene Trantham, an English teacher at Gateway School. “Radio was all anybody had to get any entertainment or news. To them if it sounded like a newscast then it was a newscast.”

In the aftermath of the broadcast, CBS and Welles were questioned while the Princeton Radio Research Project looked into the phenomena in a study headed by sociologist Hadley Cantril, compiled in The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic.

Through his research Cantril found that the broadcast frightened some listeners and not others because of three main reasons: characteristics of the broadcast, characteristics of affected listeners and situational variables.

Cantril also identified four types of listeners of the broadcast, ranging from those who rejected the broadcast as real because of internal evidence to those who fell for the broadcast without making any attempt to verify facts. The latter group made up a large portion of the million who panicked.

When looking closer at these people, Cantril discovered they were largely of the same demographic: naïve, rural and of a low socioeconomic status.

According to Pew Research Center, this same demographic of people made up a large portion of President Trump’s voter population.

“They sentimentalized and romanticized being ignorant and poor as if it were a virtue,” Trantham said. “The poor need something to hold on to. They need to feel their crappy situation makes them better people. When they see the contrary, it causes cognitive dissonance and they reject it.”

Stephen Juhlin, a Raleigh resident, said he is not surprised that those with less education are statistically easier to take advantage of, but that anyone can sell anything with enough skill.

Juhlin said he sees this demographic of people often forgotten.

“These people feel they have been losing a culture war for decades and have been forgotten economically,” Juhlin said. “They have been taken advantage of by monied interests and turned into a Pavlov’s dog of sorts that drool at the sound of the family values bell even if that bell doesn’t actually care about those values and is going to sell them out financially. The bell then blames the other for it and the cycle continues.”

Senior new media and German student at UNC Asheville Forest Gamble said he agrees uneducated people are easy to sway toward one opinion and he points to politicians using emotional rhetoric as to why.

Gamble said Trump’s every-man language makes him accessible to a wide variety of people with limited vocabularies while those like Barack Obama often use eloquent language that not every American can understand.

“Hitler in Mein Kampf says that propaganda shouldn’t target educated people, it should target people that are uneducated that are the working class and you can see that with fake news,” Gamble said. “It tends to focus on blue collar issues rather than the intelligence.”

Since the 2016 presidential campaign, fake news has come into the national spotlight with Trump claiming national news organizations who criticize him as fake news and even going so far as to offer fake news awards. Recently, television giant Sinclair Broadcast Group sent all 173 of their stations a must-run segment about fake news.

A viral video quickly circulated showing dozens of anchors at Sinclair-owned stations reading the same script word-for-word.

According to former KHGI-TV producer Justin Simmons these must-run segments are nothing new for Sinclair.

By the time Sinclair bought Simmons’s former station in Nebraska, he had been working as a video editor there for two years.

“Right away we had required segments from them called must-runs and that would be stuff like the ‘Terrorism Alert Desk,’ ‘Behind the Headlines with Mark Hyman’ and they also had several must-runs that we had to do on various national stuff,” Simmons said. “I felt like a lot of the time the segments they required us to do had a conservative slant on them.”

Soon after Sinclair bought the station, Simmons was up for promotion from video editor to producer. He said he hesitated to take the position because he did not want to be responsible for airing must-run segments, but ultimately decided to take the job because he would not be required to sign a contract.

When the fake news must-run came out, Simmons said he felt especially uncomfortable as the script closely echoed Trump’s rhetoric. This, paired with the fact that another must-run from Sinclair, “Bottom Line with Boris Epshteyn,” came from a former Trump campaign aide, left Simmons wanting to quit his job, which is exactly what he did.

“No one else was really in a position to speak out because they have contracts and a lot of those people are lifelong journalists who have families, kids, they have mortgages to pay and whatnot,” Simmons said. “I just felt like I had to take a stance so I quit my job and I spoke out about it.”

Since leaving Sinclair, Simmons wrote an op-ed for The Washington Post about his experience and has been interviewed by CNN among others.

Despite the nationwide controversy and Simmons speaking out, Sinclair remains the largest television station operator in the country both by number of stations and coverage area.

In 2017, Sinclair announced it would purchase Tribune Media’s 42 stations for nearly $4 million, bringing Sinclair’s total station count to 208. The next closest operator is Nexstar, which owns 171 stations.

The Tribune merge is currently on hold because of Sinclair’s bias and Simmons said he hopes that putting attention on this bias and the must-run segments will prevent the merger from going through.

If the merger was approved, the combined viewing households of Sinclair and Tribune would, on average, be 2.2 million households for weeknight newscasts, according to Nielsen.

According to Pew Research Center, 46 percent of Americans get their news from television and 82 percent of U.S. adults trust the information they get from local news organizations. This number goes down to 76 percent for national news organizations.

Simmons said it is important for the public to trust journalists because many reporters who work for Sinclair-owned stations do good reporting but are overshadowed by the company’s controversies.

“I understand why Sinclair does what it does,” Juhlin said. “It makes them money and pushing a conservative narrative is what is most profitable as the Conservative Party, the GOP, would love to get rid of taxes and regulations all together because it makes the people in power even wealthier. I think Sinclair should be broken up as well as other large media conglomerates and the Fairness Doctrine reinstated.”

The Fairness Doctrine was a Federal Communications Commission mandate that required TV and radio stations holding broadcast licenses to both devote time on their stations to controversial issues and to allow opposing views on those issues. Though the FCC had not formally enforced the rule in decades, it was officially taken out of the books in 2011.

Red Lion Broadcasting Co., Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission, a 1969 Supreme Court case, began the downfall of the Doctrine. Though the Court ultimately upheld the Doctrine, it was continuously called into question until it was repealed and was even revoked by the FCC in 1987.

According to Politico, the 1987 decision led to the rise of conservative talk radio as broadcasters no longer had to offer time to opposing views.

Though reinstating the Fairness Doctrine would force opposing views to be aired on the same station, some, like Ball Photo Supply employee and Asheville resident Everette Robinson, do not think it will be enough.

“Sinclair is in the business of buying up and controlling news outlets to satisfy a political agenda and probably an economic one as well,” Robinson said. “To me the recent controversy made it blatantly obvious.”

After merging with River City in 1996, Sinclair gained ownership of local Asheville station WLOS.

As mandated by Sinclair’s must-run policy, WLOS anchors read the fake news script sent out to all Sinclair stations.

“It saddens me,” Trantham said. “I grew up with WLOS as a child. It was the only TV station I could receive in Waynesville at the time. Looking back on it I felt it served the mandate of community service at the time. It gave us the local news and gave no manipulative commentary.”

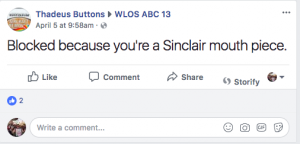

Trantham is not alone in this sentiment. After WLOS aired their reading of the must-run, dozens of viewers flooded their Facebook page expressing disappointment in the station for complying with Sinclair.

Juhlin, under the name Thadeus Buttons, commented he would be blocking the WLOS Facebook page because of their statement.

“I blocked these organizations not so much because I’m worried that I might fall into their narrative but instead to lessen their views, likes, clicks,” Juhlin said. “The less it’s interacted with the less it spreads on Facebook.”

Though Simmons said he appreciates the sentiment, he is not sure blocking or boycotting the stations will do much good.

“I wish more could be done,” Simmons said. “I’m not sure that there is much that can be done legislatively. I will say that it is unfortunate for the stations that are being boycotted because some of them still do good work but all this is kind of ruining their credibility.”

Simmons said the issue of credibility is also a big sticking point for Sinclair.

“I feel like most of that stuff occurs on social media and so the conservative script is that news outlets are spreading fake stories,” Simmons said. “The issue is that they are claiming Sinclair stories are the only ones who get it right and that’s not always the case. They’re just like every other station. People get stuff wrong. They have to issue corrections.”

The idea that social media is essential for the spread of fake news is one that Gamble is familiar with and agrees with.

Gamble said contact with one another is essential for the spread of ideas and social media only makes it easier for both good and bad information.

“Fake news is inherently viral. If you don’t have the support of a large group of people what you’re saying is not going to have any impact. By spreading lies at a grassroots level you have people talking to their neighbor who then talks to their neighbor and they’re relaying this information via this web of individuals,” Gamble said. “Nowadays it’s especially relevant because you just don’t have this peer-to-peer personal contact, you also can, through social media, see what a friend of a friend posts. You can easily share this information. In order for fake news to work, it really has to rely on this viral network.”

Gamble recently gave a talk at TEDxUNCAsheville called “Spoon Baby and the Appropriation of Evil,” where he explored the concepts of propaganda and fake news. In his talk Gamble advocates for everyone to create their own fake news in order to negate the effects of actual fake news.

Gamble said he found inspiration in his favorite communist films and the 2016 U.S. election.

“You have all these news agencies and such that say fake news is taking over social media, taking over all this but you didn’t see anybody using fake news positively, it was all negative,” Gamble said. “My idea is what if you created positive fake news that propagated positive ideas, a positive agenda that you could essentially fight this negative wave of fake news?”

Though Gamble is optimistic that fake news can be altered to become something more positive, Simmons still errs on the side of caution.

With decades of history of sending out must-runs and creating what Simmons describes as cringe worthy political propaganda, he is not optimistic that change will actually happen, but still hopes for it.

“When you have journalistic organizations against what you’re doing I feel like it’s pretty clear you’re on the wrong side of history,” Simmons said. “I would hate for more journalists to have to go through the same stuff that I did at Sinclair.”

![Brooke Pedersen [second from the right] and Luis Reyes [right] hold banners during the Wrap The Woods event.](https://thebluebanner.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ELIZABETH_PRITCHITT_IMG_3470-1200x804.jpg)