Cameron Woodyard

Contributor

[email protected]

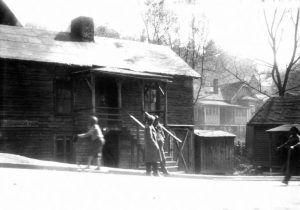

View across a paved road in a Black section of Asheville in the vicinity of Valley Street(known of as a Negro Settlement) in 1949

The city of Asheville took one of the first steps in addressing inequality toward Black residents, after tremendous efforts from the Black Lives Matter movement following recent police brutality incidents.

Asheville is one of the first cities in the U.S. to approve reparations for Black residents. The reparations resolution aims to create, but is not limited to, more opportunity for generational wealth and boost the economic opportunity in Black communities, repair damage caused by public and private systemic racism, prioritize increasing home ownership, closing the gap in health care, education and more.

“I think that’s a real mindful approach,” said Chuck Cloninger, former City Council member and former vice mayor of Asheville. “I think it’s great that they have not defined reparations nearly to just payments, because I think that would have been an uphill battle to try and accomplish.”

Buncombe County followed suit and joined Asheville in its efforts to give reparations to Black residents. The initiative does not authorize direct payments. It will prioritize creating opportunity and generational wealth for Black communities, similar to Asheville’s resolution plan.

“It would be really good if the city looked into how they could support families that are at risk of gentrification in historically Black neighborhoods, protect families from heavy tax burdens as the real estate values in the city change, and figure out ways to support African-American investment and business so that those businesses can be competitive,” said Sara Judson, associate professor of History and Africana Studies.

The evolving Black history of Asheville

Black history in Asheville is a story of segregation, slavery and discrimination. Buncombe County had over a thousand slaves and about 100 free black people, in the mid-1800s. A lawyer, by the name of Nicholas W. Woodfin owned the most slaves in Buncombe County, totaling at 122. Slaves were regularly sold through the Buncombe County Register of Deeds office and treated as property.

Now, the Black population of Asheville stands at around 10,500, which is 11.69 percent of the total population. The poverty rate amongst the Black community in Asheville is 21.45 percent.

Asheville’s culture and architecture was built off the backs of Black people who were enslaved. The labor of African slaves helped build what we know as Asheville today.

“The history of the city is bound up in Black inequality,” Judson said. “For example, the tourist industry that began here in the early 19th century was completely tied in with enslavement. Many enslaved people created the spas, the hotels and worked in places that tourists often visited.”

The city has risen to be a tourist spot with plenty of breweries, attractive scenery and the Biltmore Estate. Buncombe County had 11.1 million visitors, in 2017. Visitors spent $2 billion and generated $3.1 billion in economic impact, according to the Asheville Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Asheville remains one of the most

gentrified cities in the U.S. with the median price of homes going from $125,000 to $235,000 from 2000 to 2015, according to a U.S. census. This is partly due to the urban renewal projects that took place across the country.

Urban renewal projects began with the Housing Act of 1949, which was passed to have direct federal involvement in shaping U.S. cities as a result of people moving to the suburbs.

The Housing Act of 1949 has racist roots and the legacy of urban renewal still runs deep within Asheville. 4,000 people lived in 1,300 houses, Southside was home to 7 percent of Asheville’s population, 13 percent of city’s low-income families and half the Asheville Black population, according to a study done by the Redevelopment Commission of the City of Asheville.

The southside was predominantly Black. The Urban Renewal project, which reconstructed roads and manipulated houses and buildings, displaced most southside residents.

Past census reports indicated evidence of redlining and food shortages in Black communities because there were no nearby grocery stores.

The higher pricing for homes forced low-income Black residents to move from the area while higher-income white residents replaced them.

Asheville has grown 12.43 percent since the last censuses and more high-income people are moving here,

according to the World Population Review. The city is changing and so is its demographic. And gentrification is continuously putting Black residents at a disadvantage.

Reparations exist in America

In the wake of police brutality and voices from the Black Lives Matter movement, other cities around the country are beginning to address reparations.

“The Black Lives Matter protest created a space to address racial issues publicly,” said Bruce Cahoon, adjunct instructor at UNCA. “But this did not come out of nowhere, local activists have been addressing this issue for a long time.”

Reparations for slavery is not a new idea by any means. Scholars and activists have discussed it since the abolishment of slavery.

Affirmative action for some sort of reparations for Black Americans is a priority in some city’s agenda. For example, lawmakers in Washington addressed reparations for slavery for the first time in over a decade. Growing support for reparations for the Black community has also been seen in Portland. In Evanston, Illinois, tax proceeds from recreational cannabis sales are funding black businesses and homeowners.

Only two congress members supported a Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, in 2014. Now, 143 members of congress co-sponsor the act.

The Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act was officially introduced in 2019, sponsored by Sheila Jackson Lee, American politician. Before, congress has rejected bills that create a commission to study the consequences of slavery and need for reparations.

William Darity Jr., a well-known Black economist, argues for a meaningful program to eliminate the Black-White wealth gap. The program would cost between $10 trillion and $12 trillion.

Reparations have indeed been given in America before. Slavery was abolished in Washington, D.C., and to keep Abraham Lincoln in favor of the public he offered to pay $300 to slave owners as compensation, in 1862. The government ended up paying $300 per slave to 979 owners of 2,989 slaves. That is the equivalent of giving out $23 million in 2020 to slave owners, not the people who were enslaved.

The injustice of Japanese Americans being placed in internment camps garnered them reparations. During World War II, Japanese Americans were imprisoned in fear of spies from the Japanese government. Citizens of Japanese descent were ordered to internment camps, regardless if the citizens were born in the U.S. or from Japan, in 1942. They were not released until 1945.

The internment camps never reached the cruelty of the Nazi party’s concentration camps or the grueling history of African slavery in America. Nonetheless, it was recognized as overstepping civil liberties and in 1988, survivors were awarded $20,000 each.

A high number of Native Americans were enlisted to fight in World War II. As a token of appreciation, congress created the Indian Claims commission to compensate tribes for lost territories, in 1946. It awarded approximately $1.3 billion to 176 tribes and bands.

The largest award, $35,060,000, went to the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches of West Texas in 1974. Even small rewards were given to Native American individuals.

Africans slaves suffered many injustices. Slaves were seen as property, sub-human, and dispensable. Owners were able to torture and kill their slaves without consequence. These also violate civil liberties, but the government has not found a resolution for reparations for Black Americans.

![Brooke Pedersen [second from the right] and Luis Reyes [right] hold banners during the Wrap The Woods event.](https://thebluebanner.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ELIZABETH_PRITCHITT_IMG_3470-1200x804.jpg)