Brailey Sheridan

News Editor

[email protected]

The soft clicking of computer keys, whispered voices and an occasional child wailing fill the gaps between Kyla Morton’s words. Once or twice, Morton stops mid sentence, excuses herself, and moves throughout the building tending to the never-ending questions of volunteers, students and parents. When she returns, she laughs and continues on with her story like nothing happened – it’s all in a day’s work.

Morton, like her mom, and her grandma before her, works with children at an early learning and afterschool program at Hill Street Baptist Church in Asheville. Opening in the ‘50s under her grandma’s care, the non profit early learning center served hundreds of children from low income families during its existence. In 2015, the Christine W. Avery Learning Center opened under Executive Director CiCi Weston, affectionately termed Mrs. CiCi. Two years later, the early learning center and CWA were combined, Program Coordinator Morton said.

“Our motto is, ‘I am lovable and capable,’ meaning that everybody’s capable of being loved. That was really taught heavily in the household that I grew up in,” Morton said. “I feel like that kind of hooked up on me and my siblings, as well as my cousins, because we’ve all kind of pursued education for the most part, even as far as going to school for education.”

Women disproportionately work in occupations involving care work, which remain generally undervalued and uncompensated, according to a 2017 study by The Institute of Women’s Policy Research called The Status of Black Women. Of care work jobs, Black women occupy 13 percent of child care spaces and 33 percent of nursing, psychiatric and home health aid jobs.

Morton said being a Black woman raised by other Black women in caring roles encouraged her to also work with people, first pursuing a degree in health care and then transitioning into her role at CWA.

“We were definitely taught that we could pursue and do things as we pleased, but I definitely say being in a house full of educators, my mom and my grandma were both in the school and in the school system itself, they’ve always been a big part of that nurturer role and giving and giving back and caring for people that weren’t even family members, but just really loving and caring,” Morton said.

This gendered divide illuminates the ways gender socialization plays a role in who takes on nurturing and caretaking occupations, according to UNC Asheville Assistant Professor of Sociology Lyndi Hewitt.

“Care work of all kinds is feminized and that has always been the case,” Hewitt said. “These behaviors are not necessarily expected of men.”

Gender socialization teaches folks how to behave and interact with others in a consistent way with what society expects of their gender identity, according to Professor of Sociology Volker Frank.

“Socialization isn’t just raising a kid at home or in an institution. It’s also raising a person, making a person that has a gendered outlook that sees him-, her-, themselves as a gendered person or non-gender person and, therefore, is received accordingly by society or is told by society that they’re better and what they’re not better at,” Frank said.

Community organizer and Student Body President at UNCA London Newton, said Black women feel this socialization most, historically performing in caretaking roles in the master home.

“I think it’s all a reflection of Black women’s place in the master home that we are where we are now. Black women were in the home. White children were suckling Black women’s breasts. We were raising them. We were cooking and we were cleaning. We were used for the sexual pleasure of white men,” Newton said.

Morton said this pattern of socialization isn’t only consistent in her own life, but in the lives of the students she serves at CWA.

“A big portion of our parents, it seems like, have been in that health care role, so definitely caring for those that are sick,” Morton said. “Teachers for sure. I’ve seen a lot of educators. I think those would be the biggest two that I see. I’d definitely say they’ve been in that role to help nurture and care for.”

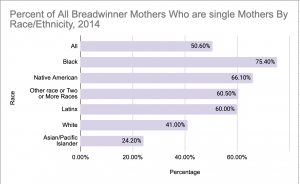

In 2019, Black women earned 21 percent lower than white women annually, illuminating Black women’s disproportionate employment in low paying care work, the Economic Policy Institute reported. Despite being paid lower wages, more than 75 percent of Black mothers serve as the breadwinner for their families.

“Historically, Black women, in society and in our family structures, 99 percent of the time are leading. We are pulling everything from scraps and keeping our families together. We are community mutual aid. We’re raising children, we’re breadwinners. So in almost every setting, we’ve been the ones running everything,” Newton said.

Today, this socialization means Black women find themselves taking on the labor of a system that continues to oppress them based on their race and gender, Newton said. Despite their position as some of the most oppressed people in the U.S., Black women remain at the helm of community organizing and building through leading protests, church groups, care centers and more. By leading these spaces, Black women can ensure their needs are attended to, Newton said. “It’s like a balance of constantly trying to make sure that my labor isn’t going to be exploited and also we’re not going to be in the conversation unless we are the face of the movement,” Newton said.

Being in these roles also allows Black women to advocate for their communities. Morton, who was placed in the Minority Medical Mentoring Program growing up, said by working in a care taking role within her community, she’s able to teach other people about medical access they may not know about, such as African-American doctors and mental health care providers.

“I have a health care background, which is strange because I’m not in health care this time, and I feel like a lot of African-Americans and minorities that I’ve met, a lot of the things that they experienced in the health care setting was because of lack of knowledge. I just really wanted to be there to provide because I felt like a lot of people didn’t didn’t have the resources to be able to get the information they needed,” Morton said.

The gravity of this work continues to be overlooked, currently and historically, Morton said. Oftentimes, because this work remains expected of Black women, they receive little to no recognition.

“I would definitely say the women in my life that I’ve seen, they’ve been given the recognition but sometimes it’s not always fair. Not necessarily that someone else was given the recognition or if anything, but the recognition wasn’t given at all,” Morton said. “What I’ve seen is they do get the recognition, but I also feel like I’ve kind of put myself in a place to be in those roles where that does happen.”

To combat some of this pressure on Black women, Morton started a preteen mentoring program for young Black women in the Asheville community called Girls ALIVE last fall.

“I feel like women already are at a disadvantage and then I feel like being Black definitely adds because it’s like we’ve already got being a woman against us and then it’s like being Black, we experienced both sides, the sexism piece, but also the racism piece,” Morton said.

The group aims to provide support and encourage self care for girls who may need a big sister figure in their lives. Morton said it remains important, especially in today’s society, to build Black women’s self confidence and to remind them that they’re capable.

“I feel like the biggest thing was seeing that a lot of the students that came into our program were growing up in a household with grandmas and aunts and some of their mothers were missing in the household. I felt like they needed almost like another big sister to watch over and love on them and give them the support and encouragement that they really need,” Morton said.

By building up young Black women and encouraging them to prioritize their mental health, Morton said communities can limit behaviors that lead to burn out among Black women, such as not asking for help or taking on too many roles.

“I would say that I haven’t seen anybody get burnt out, and honestly, even in saying that I feel like that’s one of those things that we’re taught, to be strong and not let others see you weak. So, I really haven’t seen it a lot, but I know it can lead to it for sure,” Morton said. “Just encouraging self care and taking that time for yourself. When your body says you need to rest, go ahead and take that rest.”

Due to COVID-19 and the onset of remote learning, the Christine W. Avery Learning Center needs volunteers and donations of cleaning supplies. More information can be found at www.cwalearningcenter.com.