How Zelda Fitzgerald Tragically Died on Zillicoa Street

Photo provided by Ashley McGee Whittle

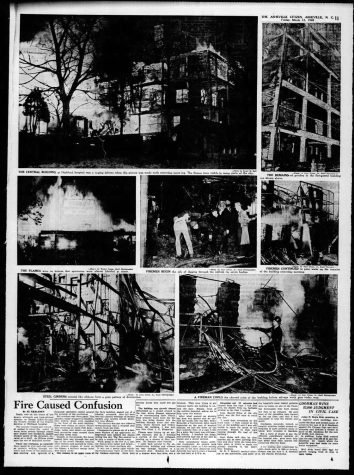

Upclose image of the fire from March 10, 1948 from the EM Ball Photographic Collection in Special Collections on UNCA campus.

November 22, 2022

Editor’s Note, Content Warning: This article contains mentions of fire, death and sexual assault.

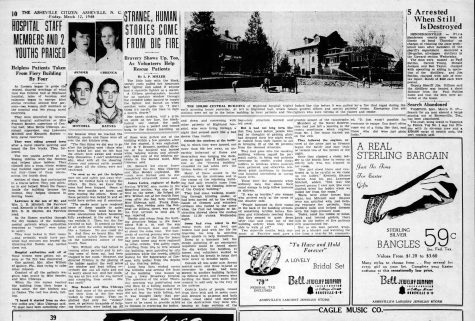

While most notable for her 1920’s flap dancing, novel “Save Me The Waltz”, and marriage to ”The Great Gatsby”’s author, F. Scott Fitzgerald, the community of Asheville tends to remember Zelda’s untimely death in the Highland Hospital fire of 1948.

“Undocumented, but often poetically written by biographers, is the story that a charred ballet slipper was found under the body,” the Historic Site Manager for the Thomas Wolfe State Historic Site Tom Muir said.

Muir said they started studying Zelda Fitzgerald and the hospital fire in order to give a presentation for the annual Zelda Festival in Asheville on March 10, 2020.

“Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, 47, Montgomery, Alabama was tentatively identified by the position of the body in the wreckage, found between about 6 and 7 p.m. on the evening of March 12, and confirmed by dental records,” Muir said.

Muir said her body was sent to Bethesda, Maryland and recovered by Rockville Union Cemetery. This was the cemetery her late husband had been buried in 8 years prior.

The Historic Site Manager said Zelda voluntarily began a three month long treatment for Schizophrenia, involving shock-treatments and high insulin doses during the month of January in 1948. In March, she had almost reached completion, and was looking forward to being sent back to her hometown, Montgomery, Alabama.

“At about 11:30 p.m. on March 10, 1948, a nurse on the fourth-floor smelled smoke coming from the dumb-waiter of the Central Building, and soon discovered a fire in a small kitchen on the third floor,” Muir said.

Muir said a newspaper writer who had rushed to the site later wrote “Death rode on the sound of low moans, whimpers and high-pitched screams as flames licked through the wooden timbers of the Central building”.

“The fire department received the first alarm at 11:44 p.m, and arrived at about 11:50 p.m,” Muir said. “The fire was deemed under control after one and a half hours.”

Muir said that fire was no stranger to the building at Highland Hospital.

“In 1917, a residence on Zillicoa Street, vacant and waiting to be renovated as housing for nurses, was destroyed in a fire originating in the basement,” Muir said.

The Historical Site Manager said Dr. Robert Carroll, son of an itinerant Presbyterian minister, became assistant director of a sanitarium at Marysville, Ohio. Dr. Carroll came to believe in “the need of the sick brain for oxygen,” between 1902-1904.

Muir said Dr. Carroll believed Asheville’s clean air and climate would help alleviate chemical imbalances in the brain, and aid depressive disorders.

“Thus, with a $5,000 investment borrowed against his life insurance, he founded his own sanitarium in April 1904 by taking over the rental and operation of the baths in the Halthenon building facing Battery Park,” Muir said.

The Historical Site Manager said the Halthenon building located at 29-31 Haywood, built by Dr. Paul Paquin in 1900 included a steam heating apparatus and numerous tubs for hot and cold baths. The building could accommodate approximately 11 patients.

“In May 1906, for $14.5k, Dr. Robert Carroll purchased property in the Montford section at Zillicoa Street and Cumberland Avenue from the widow of wealthy railroad executive Eckstein Norton,” said the historic site manager. “It included a residence and 5 acres of land.”

Muir said the Carroll residence is listed in the 1908 city directory as 75 Zillicoa St. The hospital properties were donated to Duke University in April of 1939, consisting of 50 acres, three main buildings, seven detached structures and 400 acres of woodlands.

“By 1909, his sanitarium was relocated from downtown Asheville and was renamed and chartered as Highland Hospital, Inc. Acquisition of surrounding property and construction continued for the next 40 years,” Muir said.

The Highland Home had been extensively renovated in 1926 to become Highland Hall.

“The main structures included: Highland Hall, a 40-room brick structure with offices and exam rooms and spaces for occupational therapy,” Muir said.

The manager said in 1938, plans were announced to spend $75,000 for a four-story building to replace the old Central Building, including quarters for patients, nurses and a resident physician, examination rooms, classrooms, a 200-seat assembly hall and a culinary department. The building came to a screeching haunt due to the second World War.

“I think whenever we hear about Highland Hospital we pretty much only hear about Zelda dying,” said the Executive Director of the Western North Carolina Historical Association (WNCHA) Anne Chesky Smith.

The Executive Director said at that time locals were aware that her husband, F. Scott Fitzgerald, visited the Grove Park Inn and Battery Park every now and then. After his death, most locals were not aware that Zelda was living in Asheville.

“At that point some bigger newspapers outside of Asheville picked up a bunch of stuff about it (the fire), about her specifically,” said Smith. “Locally, it was interesting that she did not seem super well known.”

Smith said the Fitzgeralds first came to Asheville around 1936, and stayed at the Grove Park Inn.

“Obviously, the two of them were not good for each other,” the executive director said. “He was an alcoholic, and she was diagnosed with Schizophrenia at the time, hopping in and out of Highland Hospital.”

Smith said that Highland Hospital originated as a Tuberculosis treatment hospital at the turn of the century. The hospital turned from Tuberculosis to a mental health facility, ultimately turning away people diagnosed with Tuberculosis as a means to cease contagion.

“The brochures said ‘non-tuberculosis patients’, similar to the hotels around because it was such a hotbed area,” Smith said.

The director said the head psychiatrist and head of the hospital, Robert Caroll, utilized high doses of insulin attempting to cure patients for upper class folks which did not seem to work.

“Because of the treatment they were doing at the time were basically huge injections of insulin that would put patients into hypoglycemic shock and really terrible things,” Smith said. “Which means that when it caught on fire they were comatose and could not get out.”

Alongside this years prior, Carroll lost his license due to multiple accounts and accusations of sexual assault.

“Carroll, within the late ‘20s, essentially was accused by a lot of young women and nurses of sexual assault and impropriety,” Smith said.

Smith said from what they can tell, the court cases traveled all the way up to the Supreme Court, but he was eventually cleared and kept running the hospital until his departure in 1939.

“I think there’s quite a bit more to that story than just what’s told, which is almost entirely about Zelda,” Smith said.

The Executive Director said WNCHA contains a copy of Zelda’s only published novel “Save Me The Waltz”.

“It’s from the Highland Hospital library,” Smith said. “It even has the library card in the back where she had checked it out for another patient, which is super cool.”

Although Zelda passed tragically in 1948, much of her memory lives on through her passion for the arts, and is preserved through historians, researchers and those within Special Collections.

“The golden Jazz Age of the ‘20s had been kind to both of them, but by the ‘30s, they were both struggling with various demons,” said the Assistant Archivist in Ramsey Library’s Special Collections and UNC Asheville graduate, Ashley McGhee Whittle.

The assistant archivist said Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald spent summers of 1935 and 1936 at the Grove Park Inn.

In the year 1936, Zelda was admitted to Highland Hospital and spent the last 12 years of her life there.

The UNCA graduate said Zelda outlived F. Scott by eight years. The famous author tragically died in 1940 in Hollywood working on his unfinished project “The Last Tycoon”. The author died from a heart attack.

The archives specialist said stories about Zelda’s life circulated amongst staff and patients well into the ‘80s and ‘90s until the Hospital officially closed in 1993 under the supervision of Duke University.

Whittle said there was a long-standing rumor that the Hospital sparked flame due to a vengeful nurse.

“Many of the patients had been sedated and locked in their rooms during the fire,” Whittle said.

The assistant archivist said nothing was ever built again on the grassy knoll which marked the place the building once stood. It is now considered a commemorative landmark.