*Information updated as of 9/22/2023

UNC Asheville enrollment is up from last fall, which means waste is also on the rise. Students cycle through piles of Brown dining hall bananas and library Smoothie Lab compostable cutlery between classes on the now bustling campus.

Yet the university is no longer composting waste this semester, despite the rising tide of waste and UNCA’s commitment to composting, as stated in the university’s Climate Action Plan.

David Todd, the Associate Vice Chancellor for Campus Operations, announced in an email to faculty and staff that UNCA lost its composting contract with Atlas Organics in August.

“Unfortunately, the company that has been transporting our materials to their composting facility is no longer providing this service,” Todd said. “Finding a new composting partner quickly is a top priority, but we do not have a contract in place at this time.”

Gracie Dotson, UNCA senior and sustainability coordinator in the Office of Sustainability, said they heard this announcement through word of mouth. No public announcement was made to the students, which Dotson said they feel is “sneaky.”

According to WNC Food Waste Solutions, composting has become a part of the entire UNCA campus culture. In November 2022, the university was listed in Princeton Review’s Top 50 “Guide to Green Colleges.”

“Students living in dorm rooms are offered compost containers for personal use, which are picked up and sent along with dining room kitchen scraps to Atlas Organics for composting,” said Marc Rudow in his WNC Food Waste Solutions article.

So how did the University lose its entire composting program?

Todd said the company, based in Spartanburg, South Carolina, has been having a hard time getting personnel to come to North Carolina.

“It’s disappointing to us because I feel like we had a pretty well developed program in place,” said Todd. “When your vendor all of a sudden stopped showing up, it makes it hard.”

And Dr. Casey King, the Director of Sustainability and a Lecturer of Environmental Studies at UNC Asheville, cites a list of challenges that come with a composting program, making it difficult to replace.

“The challenges to composting for a university who uses compost pickup or drop-off can be costs, labor and equipment requirements, improper composting, and dependence on outside contractors,” said King. “Some of the onsite composting challenges include initial setup costs, labor and equipment requirements, space provision, smell, and animal attraction.”

The state’s process for composting contracts also acts as a barrier.

“To get composting back into place, we will have to bid the contract out to two people,” Todd said. “That’s just the state process.”

Why is campus composting important?

Todd reported diverting 116 tons of waste from the landfill in the past fiscal year.

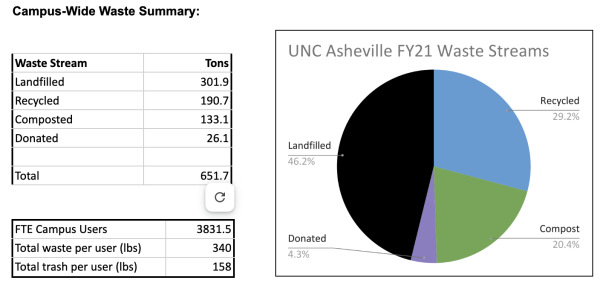

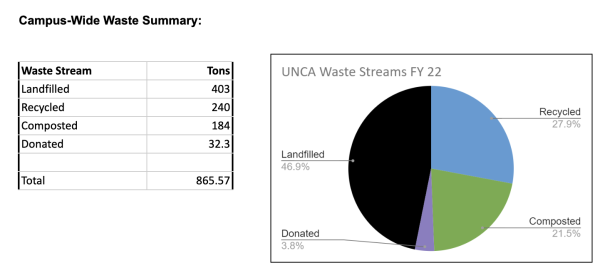

King reported that 133 tons were diverted in the 2021 fiscal year and 184 tons in 2022 fiscal year. During these years, King says campus dining had a trash diversion rate of 60 percent due largely to their comprehensive composting program. Composting has been a significant part of UNCA’s waste management across the campus since 2015, according to King.

(Casey King)

(Casey King)

Previous Chancellor Nancy Cable acknowledged the university’s need for composting in signing the 2021 Carbon Commitment, and the Sustainability Council signed the Climate Action Plan this past April.

“Composting diverts organic matter from the landfill and creates fertile soil. Each metric ton of organic waste sent to the landfill releases the equivalent amount of greenhouse gasses, mostly in the form of methane,” said the CAP.

King agrees, saying the act of composting not only helps prevent soil erosion, increase soil water retention, and mitigate climate change through storing carbon dioxide and methane, but it also provides organic material for agriculture, gardens and landscaping, stormwater management and is even used in some habitat restoration projects like wetlands reclamation.

Furthermore, composting reduces what the university sends to landfills, and Asheville’s quickly growing population is straining its landfill capacity.

But there were a few waste management bumps in the road last year before UNCA lost its composting contract.

After the sustainability office lost a co-director, Dotson, a part time student employee, managed the campus’ Race to Zero Waste initiative, which reduces university waste in competition with other schools on a national level. UNCA’s legacy of success in this competition contributed to earning a spot on Princeton Review’s Top 50 “Guide to Green Colleges.”

In previous years, Jackie Hamstead, a full time faculty member on salary pay managed this job. Dotson had 10 hours to work, and Hamstead had 40 hours.

“We did not do well in the competition and my hours were sucked up by the admin side of it,” said Dotson. “I had absolutely no time for the promotional side of it.”

Along with the halt in campus composting, Dotson is not sure if the university will participate in Race to Zero Waste again.

What can be done for now?

In 2020, The North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation commanding UNC system schools to create guidelines in solid waste reduction, and that at a minimum, the guidelines should address solid waste generated in administrative offices, classrooms, dormitories and cafeterias.

King said she is unsure about possible solutions to the university’s loss of composting.

Students could bring their compost bins, handed out from the Student Environmental Center, to Asheville composting sites, but they need a car.

Todd said he’s asked Danny’s Dumpsters, a local composting and recycling company, for a price estimate to focus on composting out of the dining hall, but Todd said they’re only a short term solution.

If a short term plan can be found for the dining hall then the university can start looking at the broader campus composting picture. However, UNCA has previously ran into different issues and a contract rebid with Danny’s Dumpsters, according to Todd.

Dotson says Danny’s Dumpsters is too small, and the company said they couldn’t handle UNCA’s size in the past.

“As a student worker who has been involved with compost initiatives in the past, I have never been told direct information about composting solutions. I know they are working to find solutions, but I have no insight on what those solutions currently are,” Dotson said.

In the meantime while solutions are found, Todd instructs the university body to continue using the campus composting bins.

“There’s still dividers for composting around trash bins so students don’t get out of the habit of composting, and when composting comes back to campus it’ll be an easier transition,” Dotson said.

King said the university’s laundry list of challenges to composting can be addressed and have been by many universities, including UNCA. These solutions contribute to climate change mitigation, provide organic material for soil improvement and reduce the volume of waste headed to the landfill.

There are cost savings options too, according to Dotson and King.

“There are grants we can apply to to have on site composting on campus, specifically at the warehouse on Riverside Drive,” Dotson said. “Jackie wrote a grant and proposed it, and it’s a part of the Climate Action Plan, but David will not let us apply for these because Campus Operations has plans for the proposed site placing.”

Yet, there may be a possibility that campus operations has plans for the Riverside space or that the space is not feasible to have compost on, according to Dotson.

Students are involved daily with the production of waste, but this semester students have the opportunity to be involved in the reduction of it too.

“If students voiced needing and wanting composting, even just the very basis of starting some kind of petition, maybe that would be enough to at least bring the conversation to the forefront of campus operations,” Dotson said.

![Brooke Pedersen [second from the right] and Luis Reyes [right] hold banners during the Wrap The Woods event.](https://thebluebanner.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ELIZABETH_PRITCHITT_IMG_3470-1200x804.jpg)