Just after I turned 7, my great-grandfather turned 90 while he was still 89. His birthday is Nov. 14. The reunion was organized so all of the cousins, aunts, sisters, brothers and uncles could come together in a big celebration of life before Grandpa Willy joined my grandma in heaven. At least, that’s how I understood the event when I was young.

That day, I wore pink fashion camo and a big Hannah Montana sticker over my heart. I remember a light breeze coming off Big Twin and the warm sun on my freckles while sitting on my dad’s lap at a picnic table. It was a beautiful day in the span of many, typical for Northern Michigan during that time of the year.

The party at my Grandpa Willy’s little red lakeside cabin, which he built with my late great-grandmother, Maxine, teemed with life. Generations of Ryckmans running through the grass and teasing each other, waiting for the food to be unwrapped. A long table was in the middle of the great lawn with bowls and bowls covered in tin foil. Children sneaked by and put their hands in the marshmallow salad, and after lunch, a thick line formed across the lawn. Everyone wanted to have a hand in churning our own vanilla dessert with an old hand-crank ice cream maker. After my turn, I tasted the salt, packed with the ice cream to keep it cold, on my hands.

This was the first time I met much of my extended family. People came from all over the country, from places like Kansas, California, South Carolina and New York, all to get together and celebrate one man. This was one of the first times I realized I was a part of something much larger than myself. I was related to almost everyone around me, and many faces were unfamiliar. I understood all of these people were connected to me because of him. I didn’t see much of Grandpa Willy at the party, but I felt the respect everyone had for this man who had such an impact on our lives. Without him, we wouldn’t be us.

*

T H E W E D D I N G

WILLARD A. RYCKMAN AND MAXINE E. RUGG

MARRIED LAST SUNDAY

Will make home in Kalkaska where groom is teller in bank

Before a beautiful background of ferns, and white tapers which decorated the parlor, Maxine Elinor Rugg, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Edward Rugg, became the bride of Willard A. Ryckman, son or Mr. and Mrs. Seymour Ryckman, at 4:30 Sunday afternoon. Rev. O. B. Anstad read the marriage vows in the house of the bride’s parents.

The Bride was charming in an ocean blue suit with navy and white accessories. Her flowers were gardenias.

Attending the bride was her sister, Mrs. Leonard Kizer, who wore a dark blue suit and carried a corsage of pink roses.

Seymour J. Ryckman, brother of the groom, was best man.

Following the ceremony a reception was held in the home of the bride’s parents, attended by members of the two families and Rev. and Mrs. Ansted.

The bridal couple left immediately following the reception on a trip through the Upper Peninsula.

They will make their home in Kalkaska, where Mr. Ryckman is employed at the local state bank.

The Leader and Kalkaskian joins their many friends in wishing the newlyweds much happiness and prosperity. *

*Reprint from the August 16, 1939, Edition of The Leader and the Kalkaskian.

*

The day after Thanksgiving, my great aunt and her childhood friend sit with Willard in his warm bedroom, shielded from the flurries just outside his window. The snow is finally sticking for the first time this season. My mom and I join the group, entering a conversation about Grandpa Willy’s latest favorite painting after some brief hellos and receiving winks from him. He always winks at his grandchildren.

“They were brought in from out west,” Grandpa muses as he points to the painting of the horses hanging above his TV. “They were lassoed and put into boxcars.”

“So that’s your dad, right, ” I ask as Mom takes the painting off the wall to pass around the room.

My great aunt, Mary-Sue, affirms the picture is of her grandfather.

Continuing his story, Grandpa says, “They came with a whole boxcar full of horses.”

Side conversations continue filling the room with subtle chuckles as the older man tells his story.

“That’s a copy of the painting right? That’s a print,” I add.

“Yes. Chris Ryckman painted that. That’s my cousin. Dad’s older brother’s son,” Mary-Sue responds.

We often talk about family who are gone, so I ask if he is still around. I never know when someone I don’t remember meeting has passed, even if we talked about them before. Mary-Sue nods and informs me Chris is now retired and made a healthy living off his career as a lung doctor. Mom struggles to hang the painting back up on the wall after we finish passing it around the room.

“You hung it crooked,” I tease. “It’s so crooked.”

Grandpa points up at the painting yet again.

“Those ponies. They were just like pets.”

Mary-Sue interjects gently, “Tell them how wild they were when you first got them.”

I laugh.

“They were wild, wild from Arizona. Yeah,” Grandpa says, making eye contact with Mom, making sure to wink before looking away.

I look up to the birthday banner, reminiscing on a card party I couldn’t attend but received photos of. The 12-hour drive from North Carolina was a little too much for only a weekend. In the photo, the small gathering occurs at his assisted living facility in Kalkaska, where we are now. Gathered around are four generations of Ryckmans, the oldest, 105, and the youngest, 1-year-old. A Detroit Lions blue banner reading “Happy 105th Birthday” is strung from the ceiling above a two-table setup with dozens of cards propped up in rows. Around 15 years ago, when family from all over the country came together to celebrate his birthday, family showed up again with a movement of birthday cards at his front door with well-wishes and congratulations for the centenarian’s long life.

Snapping myself out of the haze I buried myself under, I sniffle and pop up from my chair, deciding to lean against the back wall of the little room. I’m coming down with a cold for the second time in a month and am not keen on passing it to my grandfather, who was just in the hospital last month for fluid in his lungs.

“Were you a little kid? Do you remember these horses,” Mom asks Grandpa.

She pauses, waiting for his response, and peers up at me with a questioning look before returning her gaze to Grandpa. “How old do you think you were? Were you in high school?”

I look to my mom and swat my hand in the air in a nevermind-like gesture listening to my great-grandfather tell the room details of his childhood farm. Gesticulating fondly, he explains the horses would throw up their heads and whinny loudly when he would whistle at them with his two fingers.

The last time I saw Grandpa Willy was last August. He used to have different paintings hanging up then. One that is no longer hanging is of a snow-dusted landscape. His kids took the painting down because it reminds him of Maxine. The family likes to keep him distracted, misted in memories, omitting the bad times of his life.

When a person hits 105 years old, it is common to have memory slips. There is no way anyone can fully protect him from his own memory of lost loved ones, but we can sure try. No one wants him to spend the last portion of his life drowning in confusion with sadness as a side-effect. He doesn’t live in his little red log cabin anymore. There isn’t much Grandpa has to distract himself other than a Lions or Pistons game on the tv, visitors, and staring at the photos and paintings on his cream-colored walls.

Before the painting of the horses, he would stare at the snowy landscape Maxine’s childhood friend painted for her. Instead of telling tales of fond times on the farm and wild horses, he would cry, missing his wife and think about his time in the war. No one wants to see such a jolly man break down over lost family and a war he says “took him to hell and back.”

*

“Her name is Nora Jane,” Betsie said firmly.

“I hope you get the most beautiful doll in the world.”

Carl said with sincerity when he handed Betsie her filled two-quart pail.

Mary glanced at the threatening storm clouds. “Come Betsie. Let’s hurry home before it begins to snow. Good-bye, Carl, and thank you.”

“You’re welcome. See you soon.” Carl waved.

As they started for home, carefully carrying their pails of water, Mary said in a somber tone, “Betsie, dear, your father and I don’t want you to get your heart set on Nora Jane. You know we can’t buy so expensive a doll. We’re saving every cent we can get for a new house when we move next year, where there will be a good school for you to attend.”

“Don’t worry, Mom, Betsie began bravely, then her chin began to quiver. “You won’t have to buy her. Santa will bring Nora Jane. I just know I’ll get a doll with long golden curls.”

Then, to Mary’s dismay, Betsie began to cry and tears rolled down her little round cheeks.

“Oh Mom,” she wailed, as she looked up at Mary. “Why can’t I be like you? Why didn’t I have golden curls and blue eyes and-and be beautiful?”

The gayety fell from the afternoon.

They reached the shack after Mary had put the pills up, hung their coats and stirred the venison stew that was simmering in the cast iron Dutch oven on the stove and she sat down in the old rocking chair and rocked and cuddled her brown-eyed daughter.

Soon Betsie felt better but there was something she had to ask she began in a voice just up above a whisper. “Mom, wouldn’t you love me more if I had long golden curls and blue eyes like cousin Sarah in the picture album?”

The picture was in black and white but Betsie knew those curls were golden and those eyes were blue.

“Betsie.” Mary’s voice was firm. “What a thing to ask.”

She sat Betsie up and looked straight at her.

“I wouldn’t trade you for a dozen Sarah’s. You’re my own beautiful little girl and I love you very much. Now let’s make that Johnnycake for supper.”

The next morning two feet of snow covered the ground. Winter had come.

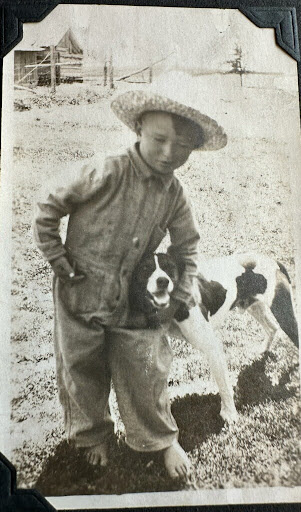

The days before Christmas went fast. Betsie spent many happy hours playing in the snow with Bing. Her outdoor clothing plus rubber boots that buckled, kept her warm and dry.

For a special fun time, Mary and Betsie would make snow ice cream. They would each take a pint-sized enamel cup and dash outdoors to fill it with the clean fluffy snow then hurry back in the house and pour a little canned milk over it and some sugar and vanilla and stir it with a spoon until well mixed. Then, they would sit by the warm stove and eat the ice cream while it was still slushy. How good it tasted!

Nothing more was said about Nora Jane. When Mary noticed Betsie studying Sarah’s picture, the album mysteriously disappeared and conversations with Carl were skillfully steered around the subject of Nora Jane.

*An excerpt from “I LOVE YOU, NORA JANE” by Maxine Rugg Ryckman

*

I watch the snow float gently down, gathering in sparkly little pillows on the window sill outside the bedroom window as I lean against the far wall.

“It was during the winter. Dad used to ice fish and she would watch dad out there,” Mary-Sue says to my mom.

Willard lays in a reclined chair in the middle of the conversation, playing ping-pong with his eyes each time a new person speaks up. He has a blanket he was gifted for his birthday with a picture of a buck on it, draped over his lap and big tan slippers peeking from under the cover on his feet.

“Did she have a job or anything,” I ask.

Mary-Sue cocks her head in question, “Who?”

“Maxine. What did she do,” I add.

“She was a teacher,” Mom responds. “But not for very long right?”

Grandpa pipes up, “She was a good teacher.”

Mary-Sue builds off of her dad’s statement, saying, “She taught when the boys were young and when Dad was in the service, but when I was growing up, she was running the office for Dad’s business. We had an office in the house and then we had a separate office, but she was the office manager.”

“She was a good help,” Grandpa adds.

“She did all the book keeping and billing, answering the phone and all of that stuff. When it was in the house, we were trained; whenever the phone rang, no matter if we were fighting or anything, everything had to stop right then,” Mary-Sue says smiling as the room bubbles into polite laughter. “The phone would ring and OOP- Hold that thought.”

“Maxine was good. She helped me a lot and she kept track of the books,” Grandpa says, smiling along with us, reiterating what he said just moments before.

I never met this good teacher, bookkeeper, poet, mother, and wife everyone gushes about. Maxine died seven years before I was born. Everything I know about her is what my family lays out onto the table for me to sift through. My mother tells me sometimes, Maxine and I would have been two peas in a pod. She was something of a creative person like myself and Mary-Sue.

It’s funny how the holidays bring up a certain air of impossibility. I drive a 24-hour round trip. Who knew I could do that? I live with my family again for a short time, and everyone knows after moving out, entering the nest again even if it is just for a fleeting while can be something like pulling teeth. I also find myself grieving those I never met, which seems like the most impossible feat of them all. The people I don’t see often all in a room at once, their collective consciousness missing the family matriarch seems to be contagious.

*

Hot tears gathered under her eyelids and rolled down her cheeks.

In the dream, Ruth recalled, Lori had stood there by the side of the bed. She was wearing her favorite dress, a full-skirted, orange chiffon, waltz-length gown that enhanced her perfectly formed body. Her hair so often tangled and in disarray, now curls softly about her face and fell smoothly to her shoulders. Lori was fairly glowing with happiness, vibrant and beautiful; a normal 17-year-old girl!

But the greatest change of all was in her eyes. Lori’s big blue eyes! They were no longer dull, or dazed, or darting in escape. They were calm and shining with love, as she had leaned over and whispered, “Good-bye, dear Mother.” how Ruth had wanted to reach out and touch her, and speak to her, but before she could do either the dream has ended.

“Oh Lorie,” She called out to her in her heart. “That was how you could have been.” And once again, as often as before, she tormented herself with the unanswerable questions. “Why did it have to be you, Lori? Why did your mind have to trap you in another world? A world of black and gray shadows.”

* An excerpt from “LORI IS FREE” by Maxine Rugg Ryckman

*

“He was in such good spirits today I didn’t want him to get, you know,” Mom says, with a photo album in one hand and a gingerbread cookie in the other.

A yellow light glows overhead as Mary-Sue, Mom and I gather around the dining room table, with tea cups and snacks strewn about in between stacks of poetry and treasured mementos. Mary-Sue nods her head in agreement.

“Yeah, he is in a bit different place than he was before where I think maybe he just misses her so much,” my aunt adds, her eyes searching through a piece of parchment from her mother’s collection of stories.

“It’s been a very long time,” I add.

“She knew he was going to live longer than she was. She told him. I don’t want you going to the cemetery, get up and shave in the morning. Go get a haircut,” Mary-Sue says, laughing ambivalently.

Her face changes, remembering a bit of the past, and continues on, “She had seen too many things. She kind of trained him to take care of himself and do the books and stuff because she always did the books.”

Mary-Sue pauses, flipping a page, “She knew.”

Maxine didn’t want, without her, for him not to remember himself.

Something I think about often is the collective grieving of Jimmy Carter on social media. In Feb, when they announced the president would be entering hospice for metastatic melanoma-related complications, the internet frenzied in a collage of memories from a life well-lived. It is a strange thing to experience something like your own funeral when you haven’t even died yet.

I find myself wondering if when my grandpa thinks about Maxine, when he gets a visitor, or when he feels his memory slip from his grasp, he is reminded of his mortality in a way that can not be escaped. Jimmy Carter is the longest-living U.S. president in history and the oldest currently-living president. He is younger than my great-grandfather.

In Nov, Jimmy Carter gave a statement about his wife Rosalynn passing away.

He said, “Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished. She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.”

What will it be like when Grandpa passes? Will everyone have already grieved because we have anticipated his absence since his 90th birthday? Even if no one says it, the anticipation and near possibility of this epochal patriarch meeting Maxine again hangs in the air every time a conversation is held with the man who has been around every single day of each of our lives. He knows, just as his wife did.

He cries with each temporary goodbye, thinking each memory made with us could be his last. His tears soak into my skin. I am reminded how my young life is only a drop in the vast tide of people Grandpa Willy has impacted in his long life. Even though we have been anticipating his passing since I was 7, once he is gone, a whole new wave of grief matching Maxine’s will flood our family, the darkness swallowing us like it consumes him. We will miss him the way he misses his wife and children and friends and siblings who passed before him. The flood will leave us drenched in the room together. Some will dry out faster than others, but the flood will affect all of us.

![Brooke Pedersen [second from the right] and Luis Reyes [right] hold banners during the Wrap The Woods event.](https://thebluebanner.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ELIZABETH_PRITCHITT_IMG_3470-1200x804.jpg)