By Jason Perry, Arts and Features Staff Writer – [email protected]

10/21/2015

For 40 years, every official document that came from the Vatican was either written by his hand or approved by his eyes.

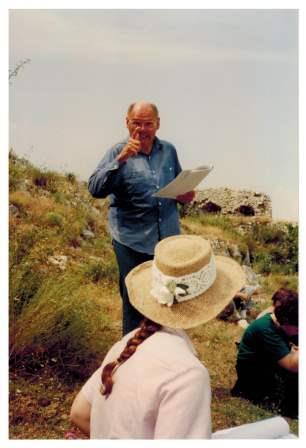

Reginald Foster, a Catholic priest known as Father Foster, was the pope’s Latinist. He is often referred to as the Latin king or the world’s greatest Latinist. Father Foster also teaches Latin, for free, to anyone willing to learn.

If they dare.

He has a fierce reputation as a teacher, writing a letter, warning his students not to come study with him.

“This class is for no superficial dilettantes,” Gregory Lyon, humanities adjunct instructor at UNC Asheville, says, recalling his letter. “If you come you will be a master of Latin.”

Every student who does study under him is required to sign a contract.

“I reject all types of childish joint-study machinations,” the document goes on to say.

Lyon says he has studied at several scholarly universities. As an undergraduate, he attended Duke University but also took summer classes at UNC Chapel Hill. Lyon studied abroad at the University of Oxford as well as Free University of Berlin. For his masters, Lyon attended Princeton University. Later, he studied as a Research Fellow at the University of Zurich. Still, Foster’s class stands out as a difficult one for Lyon.

“I was swimming,” Lyon says. “It was overwhelming how intense it was.”

Professor Lyon says his interest began in science and math. For his junior and senior years of high school, he attended the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics. Then he started his undergraduate at Duke as a chemistry major.

For fun, Lyon took medieval, Renaissance and philosophy courses. These courses satisfied his desire to understand knowledge and where it came from. He says his academic career soon shifted.

“At the end of my sophomore year I had an epiphany that one’s career should be about fun,” Lyon says. “I enjoyed chemistry, but the higher I got up in that, and was doing independent research, the more I realized that it was isolating. I was having more fun doing medieval and renaissance intellectual history. I made a big break and said that’s what I am going to do.”

Lyon says he was behind and needed to catch up in his classes, specifically Latin. He had already taken German and Spanish. Latin is not required, but if anybody wanted to go on and do graduate work, Latin is a must. All academic sources in the middle ages from the west are written in Latin, which is why learning the language is important.

Lyon started taking lots of Latin classes. He says he took Latin over the summer at Chapel Hill.

After graduating from Duke, Lyon attended Princeton for grad school. Still, he says he did not feel his Latin was good enough. Most classes teach classical Latin, which is different than the Latin that was used in the 16th century. Lyon had heard from several students of Foster’s program on how great it was. Lyon’s adviser had completed the program and recommended it because it was the only place to learn how to speak it.

Foster is one of the few people who can not only read Latin, but speak it, Lyon says.

Latin is a dying language that can be difficult to learn and understand. It is an inflected language, Lyon says, where the word ending, not the word’s position in the sentence, determines its job in the sentence as a subject or object, or the tense of the verb, or what noun the adjective is modifying.

“It’s a jigsaw puzzle that you have to recreate in your head,” Lyon says. “When you are reading Latin you have to keep everything in your head because everything doesn’t come in the word order that you expect it to come in. It’s so rewarding because once you begin to master it then you see it crystal clear.”

Lyon soon wrote to Foster asking to join his summer class. Lyon received a letter, written in Latin, warning him of the difficulties of the class and giving him an assignment. The assignment was a way for Foster to show future students how hard the work would be. It was also a way to gauge the student’s interest in learning Latin.

Lyon says he was serious.

Foster’s class only required two books. The first was the entire Oxford Latin Dictionary, and the second was a grammar book 450 pages long.

“He would provide these sheets,” Lyon says. “We would have to read the original language. He would choose texts that were difficult, give exercises and ask questions, and work you through them in a ways that were difficult.”

Foster’s class was divided into two sections: junior and senior. Each student got to pick, but Lyon says when he got there, there was no way he could do the senior section.

“I got yelled at a lot,” Lyon says. “I made stupid mistakes and he would tell you when you made stupid mistakes. He was always telling people they made stupid mistakes, and we were all in the same boat. It’s the expectation that when you show up to class you can do excellent work. He believed that about everybody no matter what their level was. To me that is a model for how to teach. Expect the best and demand the best. You accommodate to people’s abilities, yet you push everyone to do above their head. Everyone has to swim. It’s uncomfortable, but to me that was what I wanted and it’s how I try to operate.”

Foster would work in the Vatican office in the morning and teach classes in the afternoon. Class would last from 1 to 7 p.m., then he would take his class to the monastery.

“We would go back to the gardens,” Lyon says. “It was gorgeous. We would sit under the trees in the middle of summer in Rome and drink wine and beer, and he would have us recite poetry. It was living Latin.”

On Saturdays, the class would get to take trips. They visited the Forum and the Coliseum, always reading stories in Latin about the places they were visiting. Lyon says he remembers when they visited Pompeii, and Foster brought a text for them to read. It was about a young man describing his uncle’s death from the smoke at Pompeii.

“You felt like you were there,” Lyon says. “There was nothing like it.”

Before class, Lyon says he would get special permission to study in the Vatican library. It was a place that was intimidating, in order to enter one has to get past the Swiss Guard.

“They make it as difficult as possible for you to feel comfortable, especially for someone who was 23 years old and didn’t know what he was doing,” Lyon says. “There is no sign that tells you what to do, you just have to figure it out. They are not nice to you, and it’s very imposing and my Italian wasn’t very good.”

Foster also gave his students passes to watch the pope speak. Lyon says he was able to listen to Pope John Paul give a speech on why women are not allowed to be priests. Foster was a radical thinker for the Catholic church and spoke openly to his students that he did not agree with things the church did. His skills were so needed at the Vatican that the church had no way to punish him for his antics.

Lyon enjoyed his first summer studying under Foster so much he returned two years later to do it again. The second time Lyon chose to do both the junior and senior courses. Although Foster was still tough, Lyon says he recalls he was all bark and no bite. He just wanted his students to strive for the best. This is something Lyon tries to enter into his own classroom.

“Look beyond the surface,” Lyon says. “That’s something that I really enjoy teaching about this humanities program. I’m learning all of the time. I really like to go deep into texts and interrogate them. That’s what I really love doing.”

Nick Freeman, Lyon’s student, says his teaching is enthusiastic, and he focuses in depth in the material. Freeman has also heard of Lyon’s history of studying with Foster.

“I think it’s pretty awesome,” Freeman says. “I have talked to him in office hours about it just to get more information. I think it’s a pretty big deal that UNCA even has a professor that has done this.”

Brian Hook, humanities director, says he had heard several good things from two members in the humanities department before Lyon became an adjunct at UNCA.

“I have found him immediately to be deeply engaged and passionate,” Hook says. “He’s willing to contribute ideas and suggestions from the start. He is a full-fledged stakeholder in the program, and that’s how I want all the faculty to be.”

Lyon says he continues to teach and push his students, just as his former teacher taught and pushed him. He thinks to fully understand the present, one needs to fully understand the past.