Asheville Art Museum Embraces Cherokee Syllabary as “A Living Language”

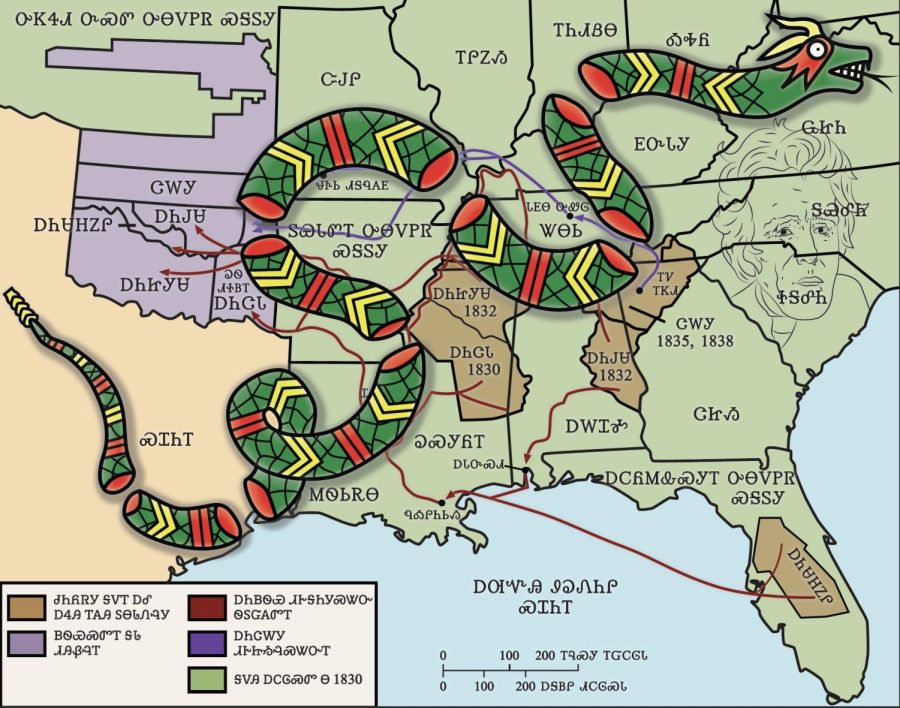

A recent piece titled, “relocate/or Die” by Jeff Edwards shows the removal of nations during the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

January 27, 2022

Now showing, “A Living Language” exhibition celebrates the cultural and national identity of artists from the Eastern Band Cherokee Indian Nation (EBCI) in downtown Asheville.

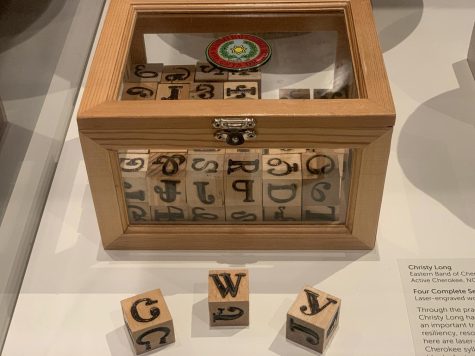

The curated works on display at the Asheville Art Museum consist of over 50 multimedia pieces by EBCI artists who direct audiences’ attention to the Cherokee syllabary. The exhibition is available to the public until March 14 and is free of charge to all degree-seeking UNC Asheville students.

The artwork defies the bias that indigenous languages are dead by uplifting local indigenous creators who help to restore the language. A variety of compositions, such as Rachel Foster’s stone-polished ceramic “Sequoyah’,’ show traditional representations of Tsalagi, or Cherokee, in cultural artifacts like pottery and basket-weaving. Likewise, the graphic designs of Jeff Edwards put on a prideful display of the syllabary and inspire viewers to want to learn how to speak it.

Foster’s ceramic is named after a Cherokee man in the early 19th-century who translated the 4000-year-old oral language into the visual and written form seen in the exhibit.

For 23 years, Barbara Duncan worked as an Education Director at the Museum of the Cherokee Indians and is well acquainted with the works on display. Throughout her career, Duncam often interacted with Cherokee people and in her friendships she was first introduced to Tsalagi. From there on, her research commenced.

“In order to make any progress in learning, understanding, speaking and teaching Cherokee, I had to radically think outside the box, along with my colleague from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, John Standingdeer. He said there had to be a pattern to the language, and when we were able to analyze Cherokee words and see their patterns, then we were able to begin to understand the language,” the adjunct faculty member said.

“Tsalagiopoly is delightfully shocking,” Duncan said.

Edwards, Cherokee Nation, contributes to the language education in schools as a language technology specialist in Tahlequah, Okla. He ensures students are equipped with the technology needed to be successful. In 2010, the artist worked with fluent speakers to integrate Tsalagi into system keyboards on devices from companies including Apple, Android, Microsoft and Google.

“What started our 10-plus years of working with tech companies is we wanted our kids to be able to text in Cherokee. That was it. Nothing more. So we worked with Apple for about 18 months and once the technology became available we saw something we didn’t expect. Our elders also took advantage of the technology. So not only were our students and elders communicating, but they were also communicating with each other,” Edwards said.

Upon completion of the keyboard, Edwards said it required careful labor to translate entire operating systems, and it had a significant impact on Cherokee people throughout the diaspora. He worked alongside Roy Boney Jr, another featured artist from his tribe, who now manages the language program.

“So, when we started translating Windows 8 we had 18 months to complete the project. We had the five regular employees and some contract translators that were from various communities. We would receive 500-1000 words a day. It is tough to say how many words were translated. It was well over the 300,000 range. But once the project was completed, Microsoft in North America recognized two languages, English and Cherokee,” Edwards said.

Despite the nation’s success in making Tsalagi accessible on major platforms, they were forced to stop working with tech companies due to the endangered state of the language. There are only 176 people still living in the Eastern Band who grew up speaking Tsalagi and an estimated 2,000 speakers left in the United States. Thus, Duncan said prioritizing second-language speakers in tribal communities remains crucial.

“I think the other compelling argument for teaching is that it is so different from European languages and European thinking. It can give insight into another way of looking at the world and language. In addition, the American Indian languages are huge intellectual accomplishments,” Duncan said.

“A Living Language” exhibit lives up to its name in its selection of pieces from Cherokee artists across generations. While navigating his busy schedule, Edwards continues to make original graphics. His latest piece, “Relocate, and/or Die” drew inspiration from Benjamin Franklin’s political cartoon intended to unite the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

“My piece is made on a backdrop of a map of the Trail of Tears and the routes taken in Cherokee. My Uktena is cut into eight pieces to represent the eight states the tribes traveled through during removal, and the Uktena has five buttons on his rattle to represent the five tribes that were forcibly removed from their homelands,” he said.

“Anger can be a very good motivator,” Edwards said.

Ultimately, what inspires Edwards the most is bringing the syllabary to the spotlight.

“I try to showcase something that all Cherokee’s are proud of, our writing system,” Edwards said.